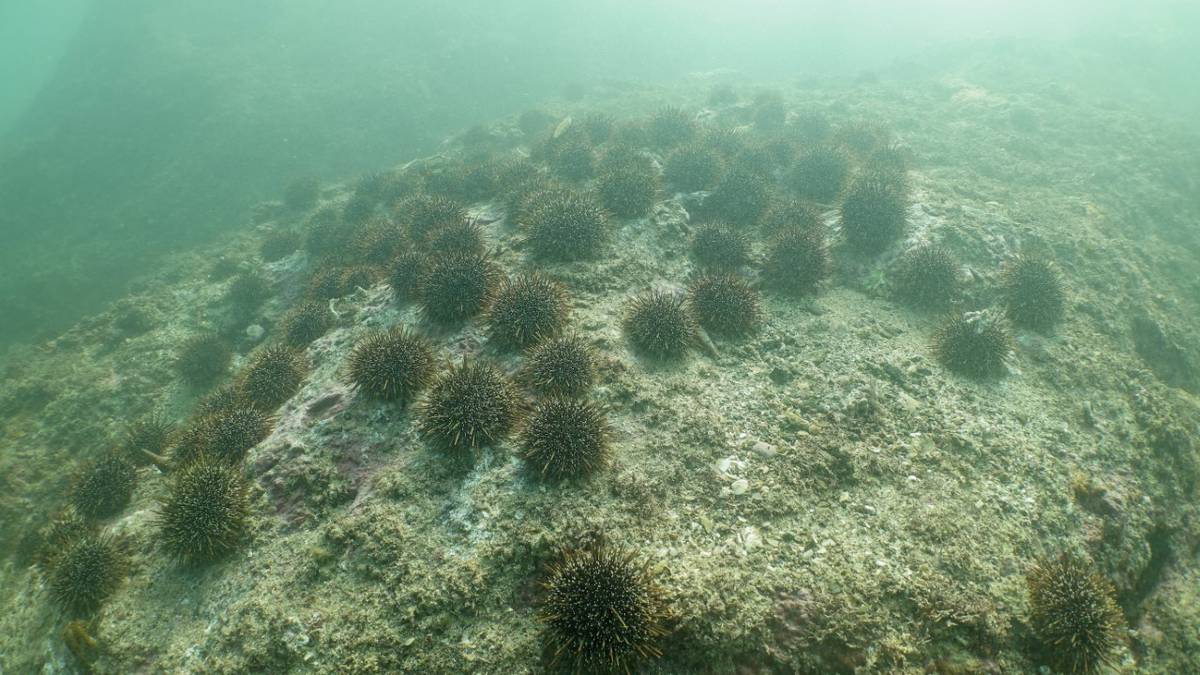

Kina barrens are caused by over-fishing of kōura (crayfish) tāmure (snapper) and other fish that predate kina. Photo / Supplied

Tūtūkākā Harbour is to become a centre for Kelp regeneration, as a community-based collaborative research project takes place in a bid to restore the harbour.

The project was last week announced by Te Wairua o te Moananui – Ocean Spirit charitable trust, which has a vision to reconnect communities with their ecosystems and return balance back to the coastal environment.

It is the lead organisation envisioning a “healthy moana” through its work, with the aid of researchers from Massey University’s School of Natural and Computational Sciences.

Ocean Ecologist and trustee of Ocean Spirit Trust Glenn Edney, spoke to the Advocate about the project, and why it is important.

“Harbours and coastal ecosystems are the most productive areas on the planet,” he said, “they are some of the most important ecosystems in terms of climate mitigation, and so they are some of the most important ecosystems for us to focus on in terms of our own wellbeing, the health and happiness of our communities, and for our survival.”

Edney told the Advocate the project has been five years in the making, and is centred around the idea that the people who are best suited to look after a local ecosystem, are those that reside there.

“Local people are the experts,” he said, “you’ve got the coastal Hapu, and there are long inter-generational relationships. We want to support mana whenua and mana moana in their roles as kaitiaki.”

The project will restore the forests of Ecklonia Kelp, which according to Edney, “are the foundations of our ecosystems”.

/cloudfront-ap-southeast-2.images.arcpublishing.com/nzme/IX2TNW6IAZBI3EZTDSVPI6TJ24.jpg)

“You can think of them as the kauri forests. Without the kauri and the big trees, you only have the forest, you don’t have any life.”

The kelp forests in Tūtūkākā are currently barren, due to the overfishing of kōura (crayfish) and tamure (snapper).

This then causes an imbalance with the kina population, which feeds on the kelp.

“When they don’t have any predators, their population can get out of balance, and their favourite food is ecklonia kelp,” he said.

/cloudfront-ap-southeast-2.images.arcpublishing.com/nzme/3BK2WPQJQBAE5KTTCODXIEEQYM.jpg)

He said the kina are left with nothing else to feed on, and an entire ecosystem can collapse.

While reducing our land use and stopping overfishing would enable the forest to return, Edney said Ocean Spirit trust is speeding up the process by “lending a helping hand”.

In their natural environment, ecklonia kelp reproduces by releasing “zoo spores”, which settle into the reef among adult kelp and grows on the rocks.

The restoration project will enable this process to occur by collecting the reproductive tissue from kelp that has washed up on local beaches.

/cloudfront-ap-southeast-2.images.arcpublishing.com/nzme/T4YR2G3AI5GN5JMS3TXU5FHGJ4.jpg)

The kelp is cleaned in order to release the spores into the water, where they settle onto stones in 17C tanks, which also have light in order to enable the baby kelp to photosynthesise.

/cloudfront-ap-southeast-2.images.arcpublishing.com/nzme/XLEY7ONIXFCS7HYJNGE5GCJYDQ.jpg)

Kina population in the area will also be monitored, in order to enable the “kelplings” to grow once they’re returned to their natural habitat.

The project has currently been occurring at Massey University’s laboratory, but will soon take place at an education centre in Church Bay.

Ocean Spirit is aiming to have the centre up and running by March next year, but restoration is due to begin on December 11.

“We are running out of time to change the trajectory for our coastal ecosystems,” said Edney, “If we don’t do stuff to regenerate those ecosystems all the policies are meaningless.”

The kelp regeneration project is part of the “Te Whanga Hauora o Tūtūkākā, Ki Uta Ki Tai Vision 2030″ to restore the mauri of Tūtūkākā Harbour to a vibrant and healthy state where kelp forests flourish, marine life abounds and our communities thrive.

There will be a public presentation about the project held at the Tūtūkākā marina office at 7pm on December 11.