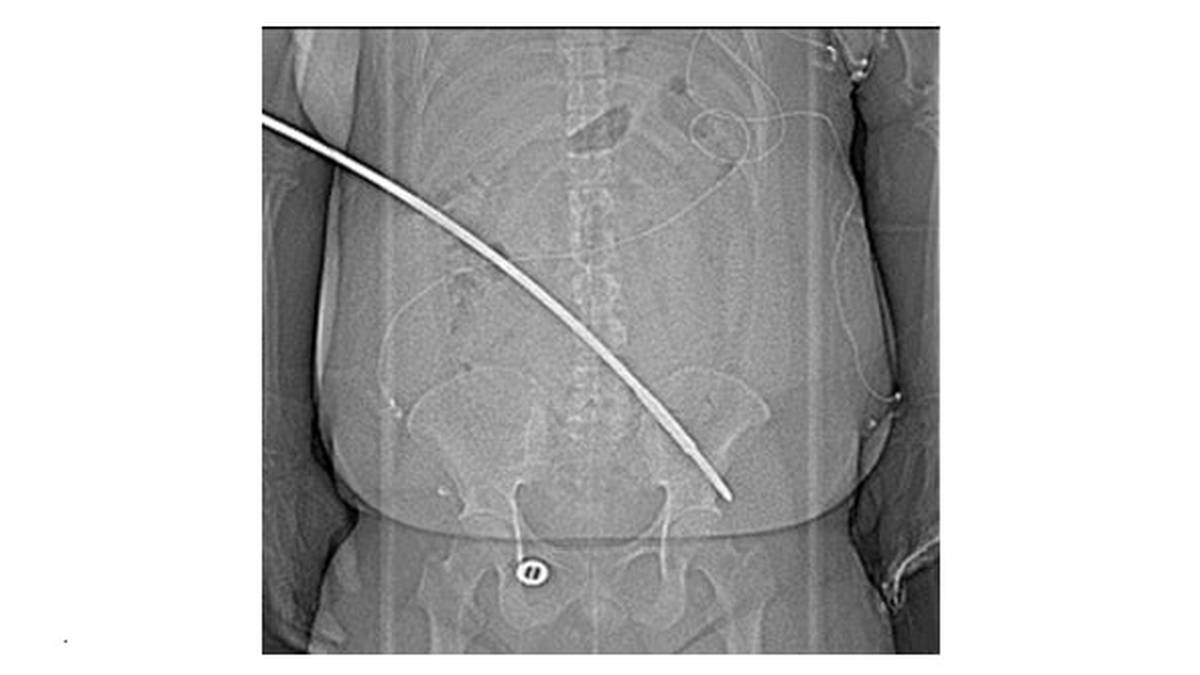

A CT scan shows the trajectory of the spear from a spearfishing gun in a man’s abdomen. Photo / New Zealand Medical Journal

The horrific case of a Kiwi man whose torso was pierced by his own speargun has given life to calls for greater regulations around the sport.

Spearfishing injuries are rare, with the sport’s enthusiasts saying

the real dangers are sharks and shallow water blackouts – nothing a spearfishing licence can protect you from.

A clinical case report published in the New Zealand Medical Journal details how a 30-year-old man was placing his loaded speargun into the backseat of his car when the spear accidentally discharged.

The spear tore through his abdomen and passed through parts of his bowel before its pointed tip penetrated the bone around his pelvis.

Fortunately, the speargun’s flopper – barb-like steel pieces that open upon contact and hold a fish on the spear once it has been shot – failed to deploy, limiting the damage caused.

Firefighters had to cut the back end of the spear’s shaft short so the man could be transported to hospital.

He underwent operations to remove the spear and repair damage to his bowel before being transferred to the Intensive Care Unit and discharged after 12 days.

The report’s authors, Auckland City Hospital Trauma & Emergency Services Fellow Dr Sohil Pothiawala and Auckland City Hospital Trauma Service director Ian Civil, note there is currently no legislation in New Zealand regarding the use of spearguns.

Users do not need a licence even though they can cause life-threatening injuries similar to those inflicted by firearms, they wrote.

/cloudfront-ap-southeast-2.images.arcpublishing.com/nzme/M7N4J6VR3VCJXMQORXIESR4ZRE.jpg)

Emma Taylor, director of Fisheries Management for Fisheries New Zealand, said they were not currently considering any changes to the rules for recreational spearfishing.

A speargun is described in the report as an atypical firearm that uses compressed air or a rubber band-propelled elastic mechanism to fire a spear at speeds of up to 975 metres per second.

Pothiawala told the Advocate that while spearfishing injuries are “quite rare”, there still needed to be a “dual-pronged” recognition of the harm spearguns can cause.

“One is to make sure that the people are aware of these injuries, and that could be done by publishing appropriate guidelines and making people more aware […] of that.”

Pothiawala said there had been some reports of spears piercing through people’s craniums and faces; even through the eyes.

Furthermore, there were reports spearguns had been used in some attempted suicides “because people know the damage”, he said.

“[…] that is why we raise the point of assessing the individual to make sure they’re competent and safe to use the firearm.”

In Australia, spearguns fall under the Firearms Regulation, meaning no-one aged 14 or younger can acquire, supply, own or use a speargun, whereas in New Zealand, they are not restricted under the Arms Act 1983.

Pothiawala and Civil suggested education, product modification, legislation and regulations as strategies available to prevent unintentional spearfishing injuries.

“There needs to be concentrated efforts to publish safety regulations and include the potential risks of speargun injuries in fishing rules,” the report read.

“In view of the potential risk of life-threatening injuries, introducing a licence requirement for the possession and handling of this firearm-like weapon needs to be considered.”

Pothiawala said that would prevent just anyone from purchasing a speargun.

Kerikeri Spearfishing Club member Steve McDonald felt a licence would do little regarding the accidental discharge of spearguns.

“In terms of safety, from what I’ve seen, everyone is really conscious of the potential harm or risk from a speargun and there are few near misses […] people are less gung-ho than what you’d think.

“We don’t just jump in there and go rip s*** and bust. It’s not an adrenaline sport, […] it’s a very well-paced and considerate sport,” he said.

McDonald had only heard of one near-miss in all his years of spearfishing, and overall, spearguns weren’t something spearfishers felt were “inherently dangerous”.

He said the real risks were sharks and shallow water blackout.

“I’m sure guys are thinking about spearguns because if you’re holding onto a knife, it’s still dangerous, but it probably wouldn’t rank as high as the other two.”

He described how recreational spearfishers operated on the golden rule that you don’t point your speargun at anyone, and never out of the water. They also mostly fish in pairs, with guns that have a range of roughly 3m underwater.

McDonald said they were always in a position where they could see their target, so pulled the trigger knowing where the spear is going.

“So the field of danger is actually quite small.”

When the Advocate approached McDonald about whether licensing should be introduced, he approached his contacts in the spearfishing community.

Among the responses was Far North local Steve Crabtree, who has been enjoying the sport since the ‘70s. His take on licensing, based on years of spearfishing in Western Australia, where a recreational fishing licence is required, had a positive spin.

He told McDonald that it was a “very effective data gathering tool” to manage the recreational fishery by informing the Department of Primary Industries and Regional Development of who is fishing for what and from where.

The fishery said all the money generated from recreational fishing licences is reinvested in initiatives that directly benefit recreational fishing in Western Australia.