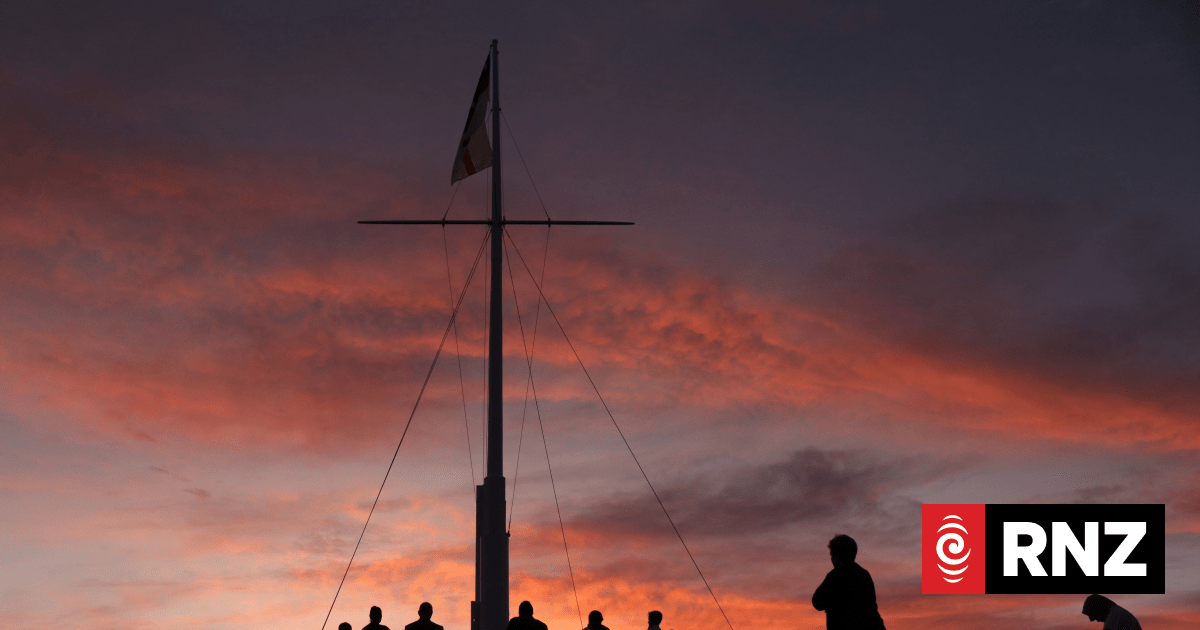

A helicopter is dwarfed by smoke billowing from the Kaimaumau fire on December 20, 2021. Photo / Lisa Everitt

No one will be prosecuted over a Far North fire last summer that cost more than $7 million to fight and took almost three months to put out.

A report released yesterday by Fire and

Emergency NZ (Fenz) found the Kaimaumau fire was accidental and caused by a permitted land-clearing burn on private property that got out of control.

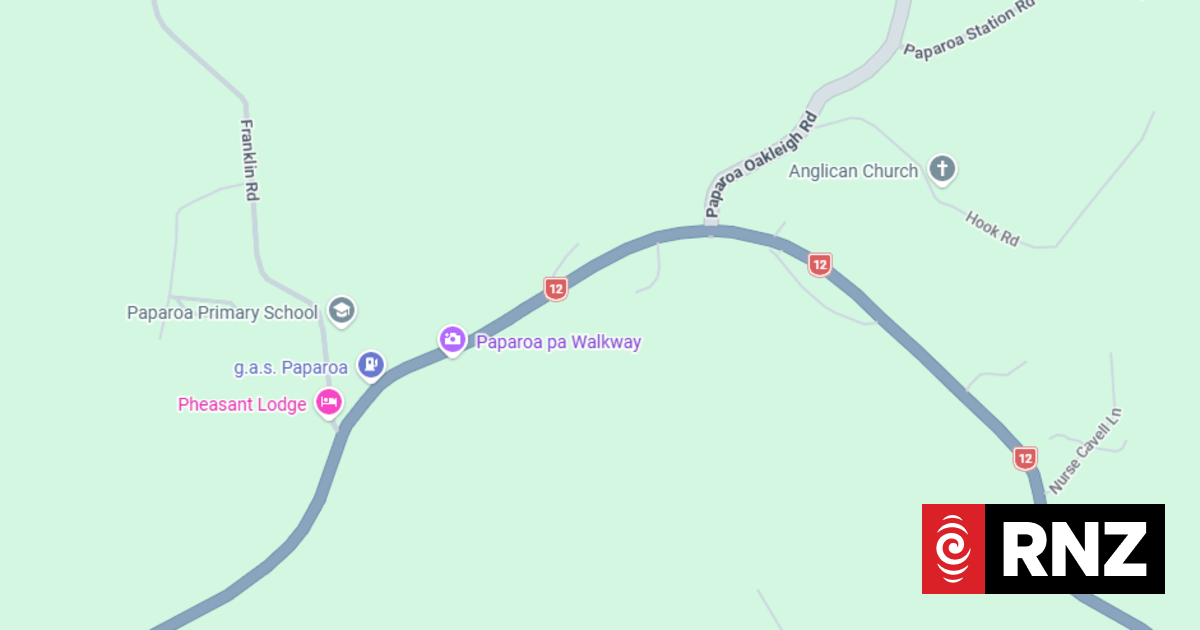

The blaze, also known as the Waiharara fire after a nearby settlement, ripped through 2800ha of a protected wetland north of Kaitāia and twice forced the evacuation of about 50 homes at Kaimaumau.

The wildfire started on December 18 last year off Norton Rd, in an area where farmland was being converted into avocado orchards, and burned until early February.

It was Northland’s biggest and most costly fire in decades.

Fenz Te Hiku region manager Ron Devlin said a number of factors contributed to the spread of the fire, including heavy dry fuels, high temperatures and strong gusty winds.

“Fire and Emergency also investigated whether there were any grounds for prosecution, and we have determined that there is insufficient evidence to carry out any prosecution in relation to this fire,” he said.

/cloudfront-ap-southeast-2.images.arcpublishing.com/nzme/H62OJKIL4ADQVKFD5VLZPPYZEM.jpg)

The 44-page report by investigators John Foley and Gary Beer found the fire started on land which had been cleared to make way for avocado growing. The name of the orchard was redacted.

The Aupōuri Peninsula is subject to year-round fire restrictions but on November 24 the landowner was granted a month-long fire permit.

Early in the week of the fire, gorse and bamboo were pushed into six piles, set alight and allowed to burn down. The remains were buried but some burning material was left exposed.

It was thought gusty winds on the morning of December 18 blew embers about 50m into the surrounding pasture. The fire then smouldered slowly through strips of dead grass and dry thatch under thick kikuyu until it reached the dense, dry vegetation of the wetland.

Locals reported seeing smoke as early as 11am but assumed it was the landowner carrying out another burnoff.

Wind gusts hit 40km/h by 1pm and the alarm was raised at 1.30pm but by then the fire was unstoppable.

The investigators eliminated other possible causes such as cigarettes, electric fences and even spontaneous combustion.

/cloudfront-ap-southeast-2.images.arcpublishing.com/nzme/DMFMXRFFJWP7NADDFRR7MRB6PQ.jpg)

About 50 homes in the beachside settlement of Kaimaumau were evacuated first on the night of December 19, with residents spending three days at Waiharara School and local marae, and again on New Year’s Day.

Later, as winds shifted and the fire advanced towards Pukenui, homes on the northern side of the wetland had to be evacuated.

In mid-January high winds brought by Cyclone Cody further complicated firefighting efforts.

/cloudfront-ap-southeast-2.images.arcpublishing.com/nzme/FSKEKH4CS7U5X6TO6IL55H7E3A.jpg)

Fenz Northland district manager Wipari Henwood said the fire was devastating for the local community and required an intense effort to put out.

“In total the fire consumed around 2800ha, more than half of which was conservation land. Residents had to evacuate twice but, fortunately, despite such destruction to the land, no lives were lost. Firefighters fought the fire for 50 days before it was safe to hand back to landowners.”

Henwood said Fenz wanted to acknowledge not only the loss of personal property but also the psychological stress the community had been under. Full recovery could be complex and take years, he said.

Devlin admitted the investigation had taken a long time.

“It’s important to us that we do a thorough investigation and take the necessary time to get it right. We appreciate the patience the community has shown, and we would also like to acknowledge those who supported the investigation and provided local knowledge and information. This helped us considerably.”

In particular, Devlin acknowledged local iwi Ngāi Takoto and the Department of Conservation’s Far North team.

The fire has yet to be officially declared out.

“While there’s no active flame or smoke at present, it could potentially be burning underground [in peat]. We will continue to monitor the fire ground vigilantly over summer,” Devlin said.

/cloudfront-ap-southeast-2.images.arcpublishing.com/nzme/6OFNLDC6VOZFBS4ORGXFP72VZI.jpg)

Figures released to the Northern Advocate under the Official Information Act showed fighting the blaze cost just over $7m in the first three months.

The biggest share, almost $4.5m, was spent on helicopters.

At the peak of the fire 11 choppers were in the air at once. Up to 80 firefighters were working on the ground along with bulldozers and diggers.

The Kaimaumau wetland is — or was — Northland’s largest surviving wetland and an important habitat for threatened species including geckos, mudfish, birds, plants and an unnamed orchid found only in the Far North.

At the time Forest and Bird Northland conservation manager Dean Baigent-Mercer called the fire “a tragedy on a national scale”.

Just over 950ha of the wetland is designated a scientific reserve while a further 2312ha is protected as a conservation area.

According to the Fenz report, the wildfire would have a lasting environmental effect on some areas.

While some native species relied on periodic fires for survival, others would be destroyed or displaced by faster-growing weeds.

The growth of woody weeds such as golden wattle could create extra fire risks in the future.

While the Kaimaumau fire was Northland’s biggest of recent times, it pales next to the Lake Ōhau wildfire of 2020 which destroyed 48 homes and buildings, led to $34.8m in insurance claims and scorched 5043ha of land in Canterbury.

/cloudfront-ap-southeast-2.images.arcpublishing.com/nzme/4473XPNMR7XJ2XGH6TUFQIM3MA.jpg)

■ The law change which created Fire and Emergency NZ in 2017 also made it harder to recover firefighting costs in cases where someone is found liable.

Before July 1, 2017, the Forest and Rural Fires Act 1977 provided a legal right to recover the costs of fire suppression from those responsible for starting fires.

However, the new law, The Fire and Emergency New Zealand Act 2017, doesn’t give Fenz any such right. Fenz could use common law rights of recovery, based for example on negligence, but that requires a higher threshold of fault by the alleged fire-starter.

Before Kaimaumau, the most expensive fire in Northland of the Fenz era was on Giles Rd, Horeke, in January 2019. It cost just over $650,000 to put out.

One of the most expensive fires before the law change was in White Cliffs Forest, Horeke, in November 2011.

That blaze was started by cycle trail contractors burning vegetation and also cost about $650,000, not counting the value of pine trees destroyed.