Lawrence Smith/Stuff

Before his death, Cian Nilsson had been reducing the amount of antipsychotics he took. (File photo)

The mental health care a 20-year-old man received in the lead up to his death was “very concerning”, a coroner has said.

The days before Cian Nilsson’s death were “happy” ones, his dad told coroner Alison Mills, he’d recently reduced his medication and seemed “more himself”.

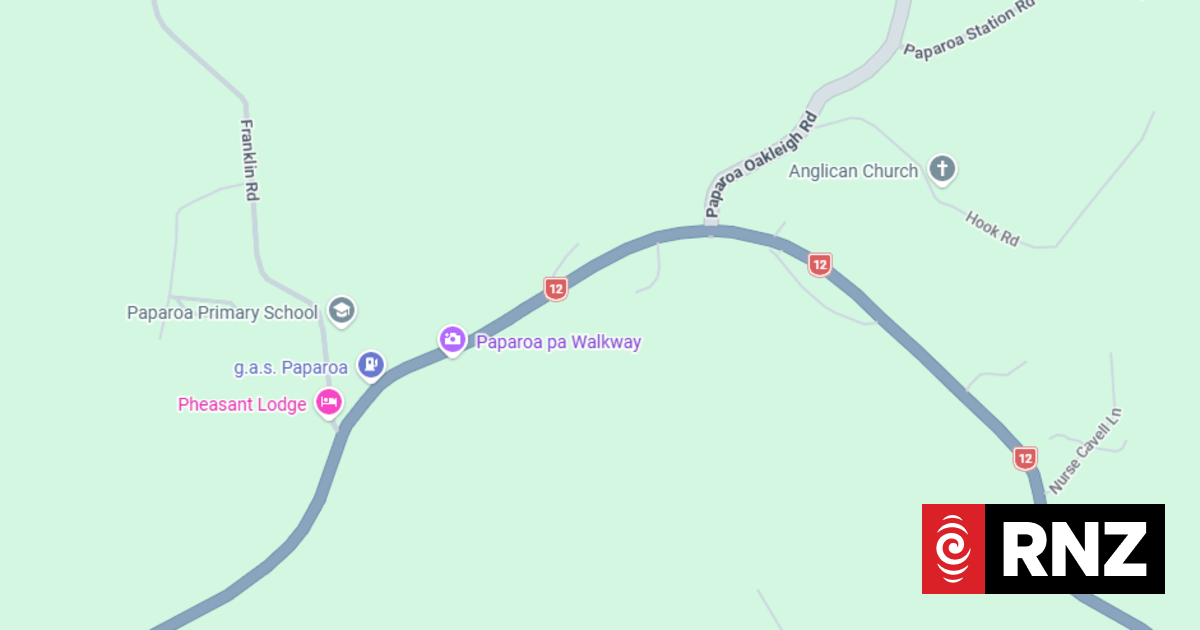

His final day was spent playing with his little sisters at their rural property in the Far North’s Peria, east of Kaitaia.

He lay in the sun on a hammock, had dinner with his family, watched a movie with his dad and made plans to help around the property in the morning.

READ MORE:

* ‘Be a friend’: Woman’s appeal following husband’s suicide

* DHB fails man who thought he was microchipped

* Family of mental health patient raise fresh concerns over report into her care

According to a coroner’s findings, the next morning, July 7, 2020, his dad found him dead after he’d taken his own life.

In the wake of Nilsson’s death, Mills found the mental health services provided to him by Northland DHB were “inadequate”, and the lack of follow-up care in his last months was “very concerning”.

Nilsson had grown up in the Far North and experienced his first psychotic experience when he was 17.

He was prescribed antipsychotics but shortly before his death he decided to reduce his dose, Mills said.

His dad Christopher Lawrence-Smith, told Mills this made Nilsson seem “happier and more himself” and as he was an adult he believed he could make his own choices about medication.

STUFF

Speaking in Christchurch, Health Minister Andrew Little said Thursday’s budget will include a $100m investment in mental health over four years.

In Mills’ findings, it was mentioned that Nilsson’s medication made him sleep for long periods of time, and he told his dad he couldn’t think properly while on them.

Mills reviewed his medical notes which showed in recent years he had significant episodes of “acute mental distress”, including psychotic episodes, delusional thoughts and anxiety.

It was noted that Nilsson believed his psychotic episodes could’ve been caused by “extensive abuse” of cannabis.

The medical notes mentioned Nilsson was difficult to contact at times, as he moved between his mum and dad’s homes and lived in a remote location, but in the months leading up to his death contact from DHB staff was “intermittent, unplanned and lacked coordination,” Mills said.

Between March and May 2020 no contact was made by DHB staff, until Nilsson initiated it. He was last seen by a psychiatrist in February that year and though a review was planned in four weeks it never happened.

The Northland DHB undertook a serious event analysis following Nilsson’s death and found a number of concerns with services provided to him.

The investigation found the absence of engagement following the psychiatrist’s assessment led to a lack of treatment interventions which increased the likelihood of self-harm.

It recommended the DHB ensure there was access to training for risk assessment and identifying suicide risks.

Mills said the lack of care planning given to Nilsson was “disappointing” – while he lived in a remote location and was sometimes reluctant to engage, she said this wasn’t unique to just him.

“These characteristics are very common, particularly in the Far North and with youth, they make the need for a coordinated care plan even more important.

“An urgent medical review should’ve been sought when it became apparent Cian was reducing his medication.

“His family should also have been made aware of the risks associated with any reduction in medication and the need for a review.”

Mills recommended the DHB review mental health services provided to the Far North to ensure there was improved communication as well as ensuring there was access to medication reviews in the area.

The DHB said it had made changes to its system it believed would improve coordination and access to medical reviews.

Ian McKenzie, general manager of mental health and addiction services, said he agreed with Mills’ findings and that the DHB had implemented the recommendations.

“Northland mental health services work hard to ensure we have an outreach approach with strong linkages to community and iwi providers.

“This includes mobile services to reach into whānau homes and schools, alongside outpatient clinics.”

McKenzie said the DHB “understood” how hard a death like this could be for a loved one and extended condolences to Nilsson’s whānau.

Where to get help

- 1737, Need to talk? Free call or text 1737 to talk to a trained counsellor.

- Anxiety New Zealand 0800 ANXIETY (0800 269 4389)

- Depression.org.nz 0800 111 757 or text 4202

- Kidsline 0800 54 37 54 for people up to 18 years old. Open 24/7.

- Lifeline 0800 543 354

- Mental Health Foundation 09 623 4812, click here to access its free resource and information service.

- Rural Support Trust 0800 787 254

- Samaritans 0800 726 666

- Suicide Crisis Helpline 0508 828 865 (0508 TAUTOKO)

- Yellow Brick Road 0800 732 825

- thelowdown.co.nz Web chat, email chat or free text 5626

- What’s Up 0800 942 8787 (for 5 to 18-year-olds). Phone counselling available Monday-Friday, noon-11pm and weekends, 3pm-11pm. Online chat is available 3pm-10pm daily.

- Youthline 0800 376 633, free text 234, email talk@youthline.co.nz, or find online chat and other support options here.

- If it is an emergency, click here to find the number for your local crisis assessment team.

- In a life-threatening situation, call 111.