Properties in Langs Beach are now selling for an average price of $2.22 million. Photo / Tania Whyte

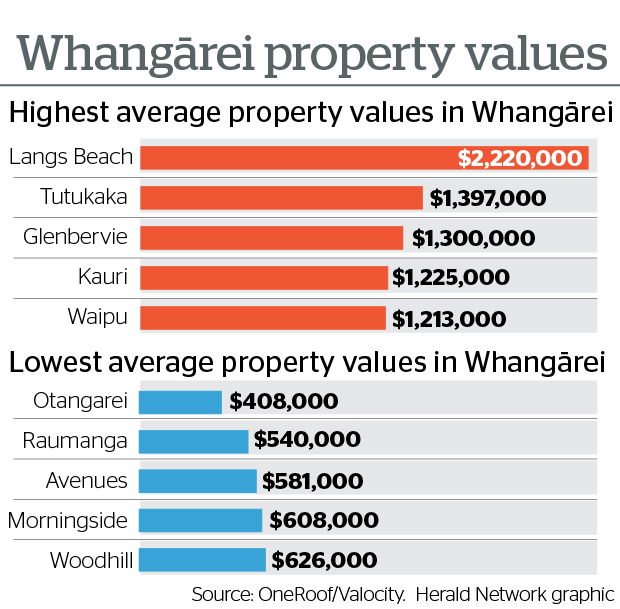

House prices in Whangārei have fallen nearly 11 per cent, but properties in some beachside suburbs are still selling for more than $2 million.

A new report from OneRoof/Valocity released today showed a drop of

10.97 per cent across the city since prices reached their peak in February.

This was significantly higher than the 5.5 per cent fall in prices across the Northland region overall, reflecting a national trend of dramatically declining house prices in cities.

Paul Beazley, business manager at Harcourts Whangārei, said it was the higher-end properties that were holding their prices.

“It’s not so much the beach suburbs, it’s more the [buyers of] high-end properties who aren’t so impacted by mortgage rates who have probably got a lot of equity.”

Buyers in areas like the Avenues, which were often in the $600,000-$800,000 bracket, were more likely to have a greater reliance on mortgages, he said.

“That’s where we’re seeing the biggest effect, because of the cost of borrowing money now.”

The rate of decline seemed to be flattening, Beazley said, but the price drops seemed to have happened in a very short period of time.

“It’s not a big drop if you go back and look at prices relative to 2019, 2020,” Beazley said.

/cloudfront-ap-southeast-2.images.arcpublishing.com/nzme/KI5T6EKL7YWVAFP2EGAF5XAIGM.jpg)

Property prices in Northland overall were still higher than last year, unlike most parts of the country.

Greater Wellington was the worst-affected region in the country, with prices falling 17.7 per cent from their peak. The overall drop across the country was 8.15 per cent, and Auckland property prices fell by 12 per cent.

Beazley said it was common for a changing market to affect the bigger centres more.

“In my experience, when you see a market shift, it’s usually more dramatic in the major cities, and in places like Whangārei, we tend to just get a ripple effect from it because our property was never overpriced in the first place.”

The suburb with the highest property prices this year in the Whangārei district was Langs Beach, where the average house sold for $2.22m. This has fallen since earlier this year, however, when the average price in the area was over $2.4m.

Tūtūkākā had the second-highest property value in the district at $1.397m.

OneRoof editor Owen Vaughan said Whangārei’s biggest sales of the year were all in beachside suburbs, and properties at the top end of the market were still selling well.

“What we’ve found is that properties that are stylishly presented, are in good locations and are renovated to a high standard are selling for good money.”

/cloudfront-ap-southeast-2.images.arcpublishing.com/nzme/ZAQLAYOHN5GEJB2H5BVJHFPP5A.jpg)

However, the biggest sales were all early in the year, with the highest-priced home, a $5.6m property in Langs Beach, selling at the peak of the market in February.

The suburbs with the lowest values were Otangarei, Raumanga and the Avenues. The average price in Otangarei was just $408,000.

Property prices in some Whangārei suburbs fell over the 12 months to the end of October, with prices in the Avenues 5.4 per cent lower than at the same time last year. Horahora properties fell 3.9 per cent.

Like Beazley, Vaughan said interest rates had put pressure on the bottom end of the market, as top-end buyers did not have the same mortgage stress.

He said the rate of property price declines had slowed, but interest rates were still rising.

“Last month, the Reserve Bank hiked the official cash rate up .75 percentage points, and the peak is still to come. There’s talk of floating interest rates getting up to 7.5 per cent.”

“That’s going to have a negative effect on the market – for investors, that means they’re going to hold off.”

James Wilson, head of valuations at Valocity, said the declining property values were likely to continue into next year, but at a slower rate.

“Expect probably more of a flat market as a rule as opposed to a continually declining market, but I wouldn’t be surprised if that could take a couple of quarters to really reveal itself.”

There had not yet been a significant drop in spending, likely because people have not yet had to fix their mortgages at a higher rate, Wilson said.

“When that happens and those mortgage rates begin to really bite, then spending is likely to dry up.

“Obviously, that has bigger economic impacts, but the key question is: will inflation be tamed by traditional policy, or will a hard, economic landing do the job? At this point, a lot of signs point to a harder landing than would be ideal.”

/cloudfront-ap-southeast-2.images.arcpublishing.com/nzme/EHNCDWAFVPIUAPOYLZUJZFQZJY.jpg)

Barfoot & Thompson auctioneer Campbell Dunoon has recently moved into one of Northland’s beach towns – four days a week. He has remained in Auckland for work three days a week, but spends the remainder of his time in Mangawhai.

Dunoon said Aucklanders moving into the area and bringing money with them had allowed for more services to come into the area.

“Mangawhai a year-and-a-half ago had very average roads, no supermarkets, just a Four Square; extremely limited options in terms of dining in cafés.

“Now, it’s got a Bunnings, it’s got a New World, it’s got major roads going through, it’s got planning approval for another 4000 houses and light industrial.

“The next thing will be medical centres. All of this is happening, and you really can’t buy into Mangawhai at all now for under $1m.”

The Covid pandemic and the cultural change to working from home was the reason behind the shift to Northland’s beaches, Dunoon said.

“Suddenly Covid appears and you can work from home, and the necessity of coming into Shortland Street [in Auckland Central] is gone.”

“I think the only reason people stay in Auckland is because their kids are there and their grandchildren are there – but once the kids grow up, there’s a lot of people who are moving to retire up north.”