The Equity Index number shows Northland as the most disadvantaged part of the country with the highest levels of socio-economic barriers to achievement. Photo / Steven McNicholl

When principal Pat Newman thinks about equity in education, his mind casts back to a Northland boy who stayed behind as his classmates went on class trips.

With five young children and not much money

to spare or spend, it was a daily struggle for the boy at home.

Newman, the Tai Tokerau Principals’ Association president, believes the new Equity Index (EQI) funding is designed to help the likes of the young boy and others in a similar situation struggling with funding to get ahead in life.

EQI is a new system introduced to replace education’s 1-10 decile rating which allocated funding according to poverty or wealth across a community. The new approach aims to finesse its way past median wealth calculations that can disguise the worst poverty and drill down into communities to meet individual needs.

Or, at least, that’s the government’s plan. The intent is to provide schools funding to support learning for every student irrespective of their socio-economic background.

While the exact funding will be revealed later this year, the national data shows Northland as the most disadvantaged part of the country with the greatest socio-economic barriers to achievement.

From next year, every school will have an EQI number ranging from 344 to 569.

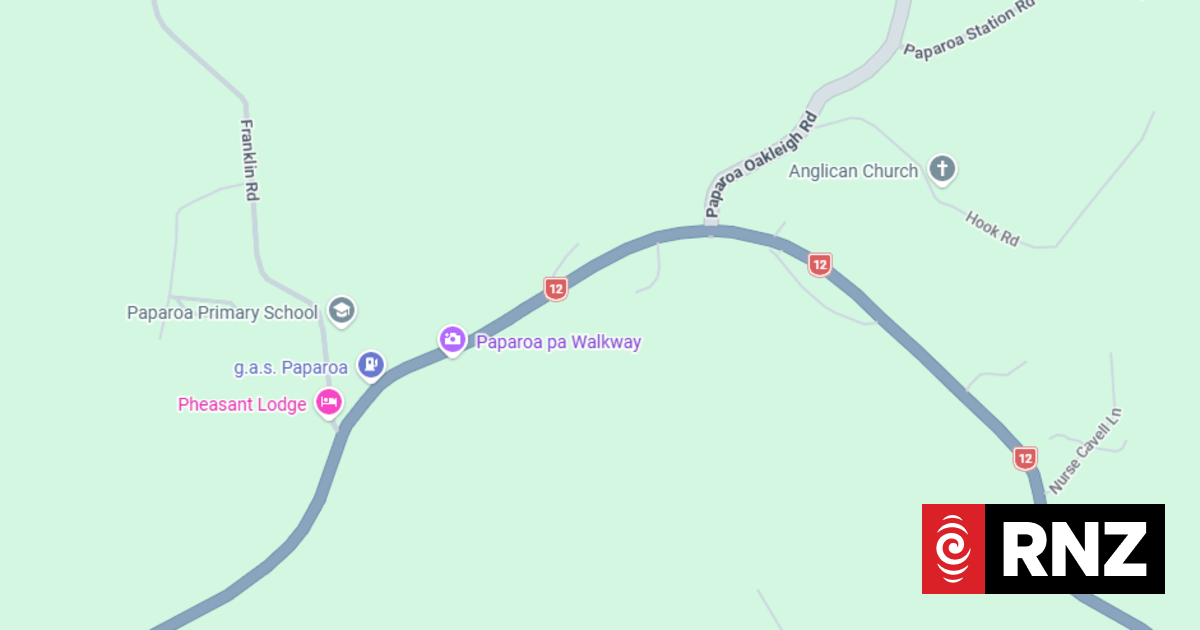

Northland’s average EQI number is 506, well above the national average of 463. Hora Hora Primary School’s index number was well into the 500s.

The higher the number, the more barriers students face in their educational achievement.

The index replaces deciles, where schools were divided into 10 groups – decile 1 being the most disadvantaged, decile 10 the least.

Previously, $161 million of equity funding was shared among the country’s 2500 schools each year, weighted towards the lowest deciles. That’s now increased by 50 per cent to $236m.

Newman said the boy he described came from a low-income household where his parents struggled financially to provide for their children. His school had done everything it could but was hampered by a lack of funding.

Newman said the EQI would help them do it better. “The additional funding will allow us to spend more effort on trying to give him an education that is not just about reading and writing but take care of the whole wellbeing without being detrimental to the income or the ability of his parents to pay.

“It means the school can provide free trips for him, so he does not have to feel whakamā (embarrassed) about it.

“We’ll be able to provide better stationery and computers instead of sourcing old second-hand ones, sports’ gear, equipment and pay his fees to play sports on the weekends.”

The new funding would lift the boy to receive the same opportunities as other children lucky enough to not suffer financial struggles at home, Newman said.

/cloudfront-ap-southeast-2.images.arcpublishing.com/nzme/U456PQRABSR3CHNKIUXYM5PZYI.jpg)

Equity index numbers, calculated using 37 socioeconomic factors, will determine a school’s share of an equity funding pool, which it can use to counteract educational disadvantages among its students.

Kaeo Primary School principal Paul Barker was not yet convinced the new funding would be enough to bring much change. He said Northland had always been at the top of deprivation needs.

“Sitting at the top of the needs pile does not necessarily mean we get the top of the support.”

Barker said the EQI number was derived without the input from principals, “in secret” and they had to take the Government’s word for it.

/cloudfront-ap-southeast-2.images.arcpublishing.com/nzme/V7KM3KPVNP4ONZJJZU237OEJFY.jpg)

“We do not know which of our kids have been identified to make up the equity index… we can’t even check whether the number of kids they have identified is appropriate or not.

“When I look across my school, I clearly know who right now is struggling, but I don’t know if those families make up the ones identified to contribute to the equity index data.”

Kaitaia Primary School principal Brendon Morrissey argued the outdated decile system had nothing to do with schools or the kids in schools, while the equity index did.

“The previous decile system was based on socio-economics and the main criteria were how many people live in a house in a community, what is the average income per house in the community, what is the average level of adult qualification in each house in the community; where did school come into any of that.

“The funding of the equity index is based on the kids that are in your school.

“And all of the information that we can find about their families, their lives, and things that might make it difficult for kids to succeed, you would want to put more resources to make that less of a barrier.”

/cloudfront-ap-southeast-2.images.arcpublishing.com/nzme/RC2IOEMT2WOMXGM5HI34W57BWE.jpg)

His is a Decile 1 school with an Equity Index number of 549, right up at the high end of the scale.

The equity index funding could be a real blessing for a school like his, Morrissey said.

“We have learned an amazing amount of stuff over the last decade on how to help our kids who have those needs… have bent over backwards doing the best we can, and we have done that without enough resourcing.”

Morrissey said the EQI could put enough funding directly into schools to have that expert help on site every day.

“For example, we can maybe employ a social worker on staff, a person with a medical background, counsellor, speech therapist, and so on.

“We are not in a city; we do not have the amount of resourced people and expertise the schools in cities have. We are an isolated school and we lack the resources the other central schools have.”