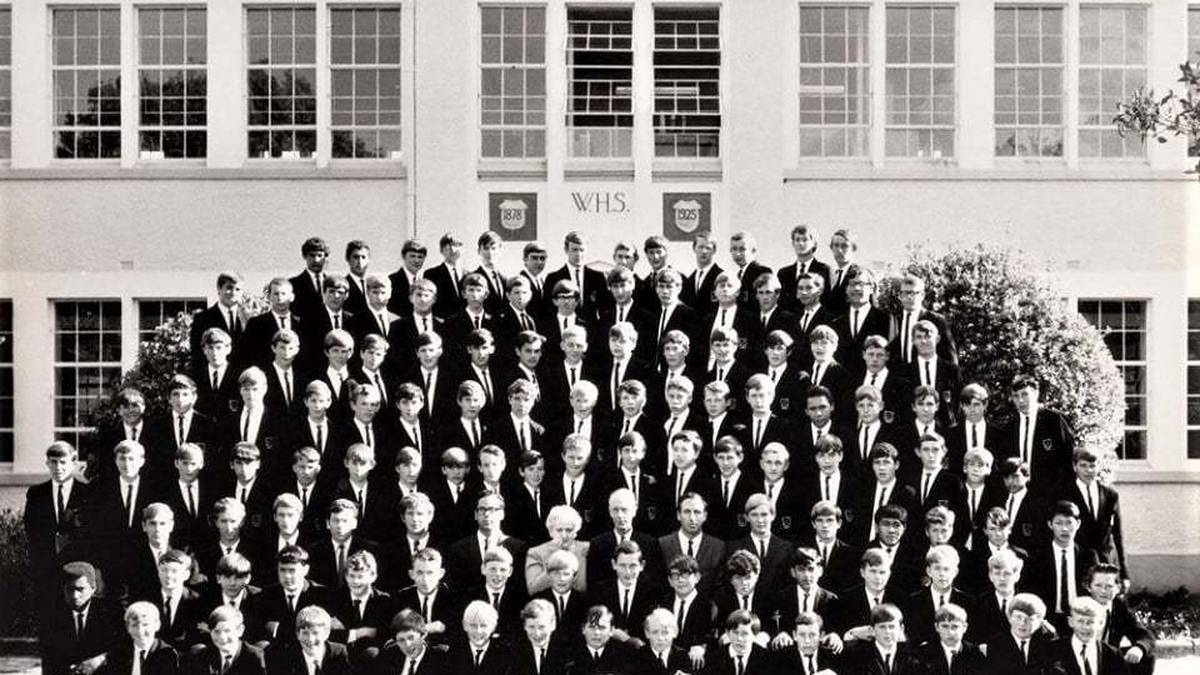

Carruth House boarders in 1969 including Steve Herbert who attended the school from 1965-1969. Photo / Supplied

In the wake of the recent announcement that the Whangārei Boys’ High School boarding hostel Carruth House will be closing at the end of the year, the Northern Advocate has caught up with some of

the Carruth old boys and a former employee who share their wild and wonderful memories.

The gods must be crazy: Culture shock for the boy from Tokelau

Isopo Samu was 11 when he was put on a boat that sailed from the tiny South Pacific atoll of Tokelau, which is home to about 1500 people. This was in 1973.

After three days at sea, Samu flew in a plane for the first time and landed in Auckland, which then had a population of over 600,000 people.

/cloudfront-ap-southeast-2.images.arcpublishing.com/nzme/2AMYJ7FSOTSDRCGP3UFCNUT4LQ.jpg)

“Do you know the film The Gods Must Be Crazy? It was like that – a real culture shock,” Samu said.

His long journey didn’t end in Auckland. A 3.5-hour bus ride brought the little boy north to Whangārei.

“I was freaking out on the bus because I thought the bus driver would run out of land.”

Samu was dropped at the Whangārei bus station together with another kid, and they both sat on their suitcases crying until finally, someone took them to their new home: Carruth House.

On his first day, all boys were weighed and then put up in a fight against another boy.

“I was one of the smallest and I had to fight a 4th or 5th former.”

That was Samu’s initiation to Carruth and, for a kid who didn’t really understand English well, it was hell.

“There was a lot of name calling and bullying in my first year. I was the smallest by far.”

There were some older boys from the islands and while they didn’t necessarily look out for him, other kids left him alone when Samu stayed close to the group.

He said you learn to survive and stand up for yourself very quickly and at the end of his seven years at the hostel, Carruth was his home and the boys were like his family.

“I had lost the sense of having a family. I didn’t see my mother for eight years.

“Didn’t realise how much it affected me until I had children of my own.

“When they turned the age I was when I left Tokelau, I was really short with them because I didn’t understand why they were so dependent.

“My wife realised what was going on and said, these kids are not you.”

As the oldest of seven, Samu had received a scholarship to study at Boys’ High but in those days there was nothing in place to ensure the emotional wellbeing of the kids, or anything to preserve their cultural identity.

“I went through a period of identifying strongly with Māori and pākehā and not my own culture. I lost a lot of cultural identity.”

/cloudfront-ap-southeast-2.images.arcpublishing.com/nzme/5FNSOFQVD4KI5FNVAN3R2HLKKY.jpg)

He first returned to Tokelau after he graduated from high school when he was 18 or 19 and felt like a stranger – and he still does to this day. “It’s almost like I’m a tourist when I go there.”

Despite this rift, Samu doesn’t feel resentment towards his parents for sending him to Whangārei.

“When you’re parenting you’re trying to do what’s best for your kids with the resources you have. And that’s what they did.

“Being at Carruth was a privilege. That place made me. It’s about attitude. I look at the experience and be angry, but I’ve decided to view it as a blessing.”

Today, Samu prefers not to identify as an islander because it sets up barriers, he says. Instead, it was about being a good person.

He is a local business owner and runs a mentoring programme for young people. He even returned to Carruth to run the hostel for a couple of years.

Samu also maintains contact with the Carruth boys he went to school with and when they catch up, “it’s like we just spoke yesterday”.

Lots of stew: Hostel cook recalls Carruth menu

In the late 1980s, Waana Beazley Reihana started arguably most important job at Carruth – she became a hostel cook.

The ladies in the kitchen had the never-ending task of filling the growing boys’ tummies and were an integral part of the home life of the hostel.

“At the time I was there, Pam and Bob Walters were the house parents at Carruth. They are the managers of the hostel and lived there 24/7 to watch over the boys,” Beazley Reihana explained.

There was also another set of house parents who took over when the Walters had a day off.

/cloudfront-ap-southeast-2.images.arcpublishing.com/nzme/4OE47I5PCU5DGTYHIJ5F2TGXMM.jpg)

“The house parents made sure the boys behaved. The kitchen staff prepared all the meals. There were four of us working different shifts. Then there was laundry and cleaning staff.”

Her shift started at 6am with breakfast.

“The boarders had cereal for breakfast, nothing cooked. And then we packed their lunches, usually a sandwich.”

On the dinner menu, there was a lot of stew, Beazley Reihana remembers, as well as schnitzels, big sausage rolls and fried fish on Fridays.

At the time she worked there, most Carruth boarders came from out of town. One of the boys was from Australia and there were a pair of brothers from Fiji.

“It was like a big home. The boys were well behaved.”

Corporal punishment was still a frequently used tool by the house master, whose office was right next to the kitchen.

“We could hear the caning in the kitchen,” Beazley Reihana said. Kitchen ladies would sometimes slip a little treat to the boys after their hiding.

Beazley Reihana said it was sad to see Carruth closing. She went to boarding school herself and so did her grandson.

Nose in the book: The shy farm boy who escaped rural life

For Steve Herbert, his life as a teenager in the 1960s would be either early mornings and hard work in the cow shed or sharing a dorm with 24 boys at Carruth.

Neither option was particularly appealing to the Okaihau farm boy, but the boarding hostel at least gave him some exposure to creatures other than cows.

“Our district school was reasonable, but I got specially chosen because I was apparently the smart one in the class.”

The principal convinced Herbert’s parents to send their boy off to Whangārei back in 1965, which was a “mind-bogging” experience to begin with.

“It was all new. I’ve never been away from home and I was quiet and reserved.

“At the start, I tended to walk around with my nose in the book. I certainly gained a lot more confidence over time.”

/cloudfront-ap-southeast-2.images.arcpublishing.com/nzme/AALDFNSMIIKIOXXTBVYKT45WME.jpg)

During his time at Carruth, the days were very structured. The senior boy in Herbert’s dorm ensured all students were up “nice and early”, made their beds and did their press-ups.

“He was making sure that we’re upholding the values of Carruth,” Herbert said.

“There was more pressure on us to do well and do the right thing. I fell into line as a young boy growing up.”

Even after school was finished, the Carruth boys had an allocated time – 6pm-8pm – to do their homework. At 9pm sharp, the lights were out.

Part of being a Carruth boy meant playing sports and joining the fierce competition between boarders and day boys. It was mostly rugby in winter and cricket in summer.

While the boarders usually spent their weekends at the hostel, they were sent home over long weekends and the holidays.

Herbert remembers fondly a little cheeky adventure when he failed to tell his parents he was due to come home one weekend after a cricket match.

Because no one came to pick up Herbert, he spent the weekend happily roaming the empty halls of Carruth hostel all by himself. No one ever found out.

The now-semi-retired teacher says while his time at Carruth was challenging, there was a sense of belonging among the boarders.

To distinguish themselves from the day boys, they used to wear their school caps with a little peak, Herbert said.

“Boarding school is not for everybody, but for the majority of us it was good. I never got homesick.

“Kids these days enjoy more freedom. If you live at boarding school you have to abide by the rules.”

/cloudfront-ap-southeast-2.images.arcpublishing.com/nzme/7SHNCCXJ2FZL6HD765WB7FZGAM.jpg)

Highly illegal escapades: Post-war Carruth and the Sally Lunn bun shop

If the 1960s at Whangārei Boys’ High sound strict, then the 50s appear almost like a military camp.

But despite the frequent scrutiny from teachers and masters, John Elliot, who was at Carruth from 1952-56, looks back fondly on his time.

Elliot’s parents, two well-educated people who wanted to see their son excel at school, sent their son from their farm in the Bay of Islands down to Whangārei.

With only six years since the end of the war, many of the teaching staff had been part of it and “weren’t taking any nonsense from snotty-nosed teenagers”.

“We tended to be in awe of our masters. One of our teachers had commanded the Māori Battalion.”

The Carruth hostel that was used as a hospital during WWII wasn’t the physical memento from war on the school grounds.

There was an armoury in the basement of one of the school buildings that predominantly held .303 British rifles that were owned by the army.

The school regularly organised a cadet week when students were handed these fully operational rifles – something that would be unthinkable today, Elliot said.

“Some boy could have easily assassinated the whole staff.”

Elliot’s mornings used to start brutally with someone bashing a drum outside the hostel to wake up the boarders. All boys had to get out of bed, get washed and ready, make their beds and wait for inspection.

“Any infraction meant two strokes of the cane on the bum.”

For breakfast the boys had “porridge with big lumps”, and there was a strict rule in place that banned the boys from dropping their cutlery on the floor.

Every time the sound of a spoon clattering on the concrete floor rang through the dining room, everyone went dead silent and the culprit had to walk up to the house master’s table at the end of the hall and formally apologise.

The post-breakfast inspection ensured the boys’ shoes were polished and their hair cut short.

“You had to feel the bristles at the back of the head.”

Despite the strict rules and expectations towards the students’ conduct, Elliot and his fellow Carruth boys got up to “all sorts of escapades”.

“At the end of school, we were not allowed back at the dorm before dinner. They didn’t want us lounging around creating chaos.”

To pass time after school, Carruth boys were encouraged to play sports – especially hockey and rugby, Elliot remembers.

“One boy asked once if we could introduce league. And the headmaster replied; ‘As long as I am headmaster at this school, league will never be played!’.”

Parents could also deposit pocket money for their sons with the school that would be handed out gradually over the term.

“I spent most of my money on books,” Elliot said. “We were great on war stories about beating the Nazis.”

/cloudfront-ap-southeast-2.images.arcpublishing.com/nzme/G77KO4KA6YEGG5YD7G3CZ2HDTY.jpg)

Over the weekends, the boarders were allowed to go into town, as long as everyone returned by 5.30pm.

One popular excursion for the boarders was a trip downtown. But even outside of the school grounds, students had to exhibit flawless manners in public.

“If you met your headmaster in town you had to lift your cap and say, ‘afternoon, sir’.

“Sometimes you would whip around the block and confront the headmaster again – ‘afternoon, sir’!”

While Saturday was usually earmarked for sports, on Sunday afternoon “no one cared where you went as long as you were back for roll call”, Elliot said.

“We used to go all sorts of places – some would be regarded as highly illegal these days.

“The thought of being caned if you’re late for roll call was worse than the thought of being killed.”

Elliot would receive about 10 hidings a term, he said.

“On Sunday mornings, we were all expected to go to church which was regarded as incredibly boring.

“We got well adapted in the deaf alphabet. You can hear interesting conversations at the back of a pew.”

Films nights were also on the agenda, showing movies by Alfred Hitchcock and with Jimmy Stewart – “certainly no porn” though.

“Twice a term the girls from Lupton were invited over for a dance. There would be a band – usually the Newberry Brothers.

“For many of us who were totally socially inept in female company, the dance wasn’t an enjoyable event.”

One of Elliot’s main memories is being hungry “the whole bloody time”.

“Not because we weren’t fed properly, but because we were growing teenagers.”

Outside the school ground used to be a tuck shop run by Mr and Mrs Hawking who sold “all sorts of unhealthy stuff”.

“One of the favourites for the boys were Sally Lunn buns with coconut icing and raisins.

“One Sunday, Mrs Hawkins had lots of Sally Lunn buns left over so she cut them in half and gave three trays to the two prefects to share with the hostel boys.

“[The two prefects] set up shop at the Carruth wall and flogged off the whole lot.

“On Monday, the matron asked the boys if they had enjoyed their Sally Lunn buns and everyone asked, ‘What buns’?

“The two prefects were expelled on the spot.”

The Sally Lunn antics showed just how strict the school was at that time, Elliot said, but despite that – or maybe because of it – there was a “great sense of camaraderie among the boarders”.

“I enjoyed my time at Carruth. It was a great school and I had teachers who took an interest in us.”