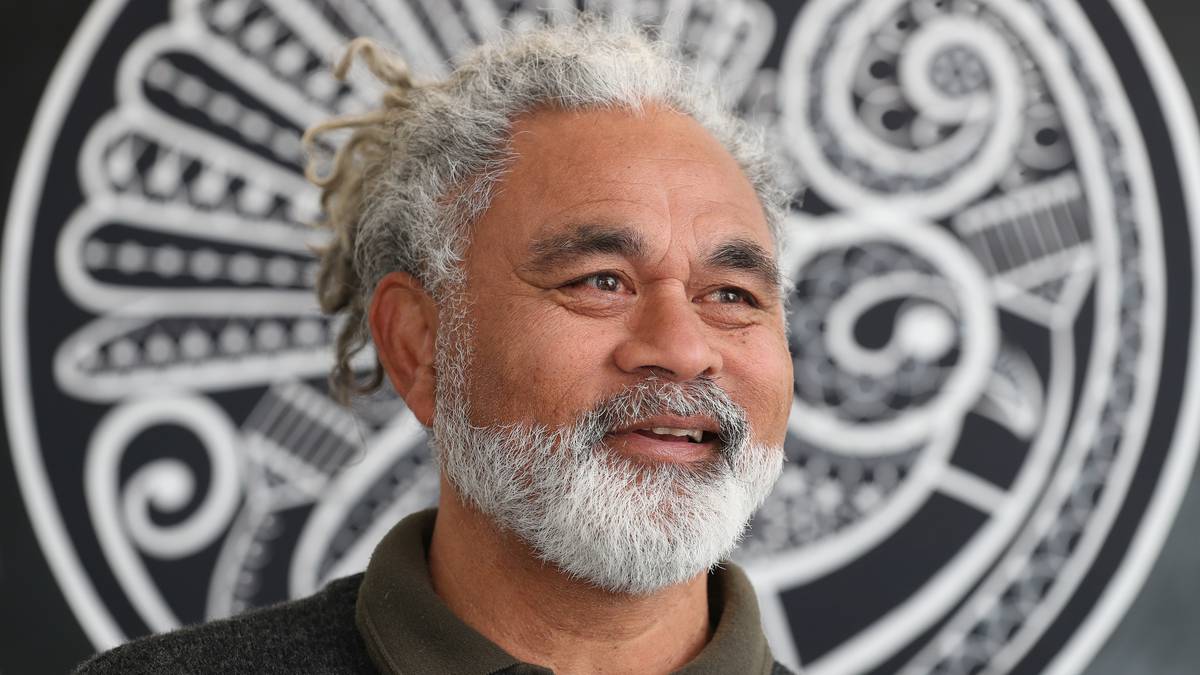

Isopo Samu of Tokotoko Solutions wants to see barriers to and from Alternative Education lifted. Photo / Michael Cunningham

Teens unable to return to the traditional classroom end up living on the benefit or gaining criminal convictions because the education tool designed to help them is underfunded and under-resourced.

Students who struggle in mainstream

school, either because they are neurodivergent or within the justice system and/or under the jurisdiction of Oranga Tamariki, are often placed into Alternative Education (AE) to help them transition back to school, training, employment or other education.

But educators say the system is failing and the effects on youth are devastating.

According to recent research, fewer than one in 10 young people in AE go on to achieve NCEA Level 2. By 18, more than a third of AE learners had police proceedings against them, and by 20 almost seven in 10 were beneficiaries.

Isopo Samu, founder of AE provider Tokotoko Solutions, believed a severe lack of funding for AE and a “bottleneck” in mainstream schools had stopped rangatahi (young people) from getting ahead in life.

Samu said a student in Alternative Education receives less than half the amount of funding as a student in a small secondary school.

“Alternative Education was never meant to be the destination, it was always meant to be a stop. It’s like a bus stop – you stop off, get where you need, jump on the school bus and get back to school.”

But “once outside the system, you’re stuffed”, Samu said.

Te Tai Raro deputy chief executive Ruth Shinoda said AE is failing despite the hard work of the young people involved and those working with them.

She said those in AE had significantly worse outcomes than other young people.

“We know that the long-term costs for these learners, their whānau and society can be devastating.”

Samu said his students come with a raft of complexities and staff were often having to fill gaps in their education that stretch back to primary school.

Samu’s observation is that schools have shifted their priorities from a focus on individualised learning to the “achievement quota”.

“What’s happening now is that we’ve got a bottleneck at the schools. The schools are putting up barriers for these kids to return to school.”

He said if schools were invested in bettering the outcomes for students in AE, they would see the external providers as a resource.

The Education Review Office (ERO) released a damning report about AE, but Samu said the programme maintains a great attendance rate – around 95 to 100 per cent at Tokotoko Solutions.

Of the nine students to leave Samu’s programme last year, seven went on to work and two returned to school.

The ERO reported students felt safer, more welcome and cared for in AE than at their school.

Ministry of Education acting leader of Te Rai Raro (North), Leisa Maddix, said the ERO’s review of AE is consistent with the direction the ministry hopes to take when redesigning AE.

That direction includes creating stronger relationships and collaboration, flexible and learner-centred provision, more skilled staff and adequate funding, she said.

But funding constraints mean the changes will occur gradually.

Brodie Stone is the education and general news reporter at the Advocate. Brodie recently graduated from Massey University and has a special interest in the environment and investigative reporting.