A Vietnam War veteran has shared details of a $15,000 life insurance policy that most recently cost him $5800 a year.

Over 20 years, the Kaitaia man paid $43,000 in premiums on the policy –

almost three times the amount it would have paid out.

“I feel like I’ve been ripped off,” said the former soldier.

He wasn’t – it’s just the way life insurance works for older New Zealanders.

The case has prompted Retirement Commissioner Jane Wrightson to state that insurance companies should be proactively asking questions of older clients to make sure the cover they have is what they need.

And one expert says most middle-class New Zealand families can pretty much do away with life insurance by the time they hit 50 because there is usually enough of a financial cushion to ride out the worst of times.

The veteran is a quietly-spoken man from Kaitaia who shared details of his policy but sought anonymity after a life of military service and private military adventuring.

Now aged 84, he’s literally a man of a different age with adventures that read like a Wilbur Smith novel.

Given some of those adventures, it’s remarkable he had a life left to be insured. They include service in Vietnam where he was doused in Agent Orange, fighting as a member of the former Rhodesian SAS, enlisting with the Sultan of Oman, training German special forces on hostage rescues.

Those adventures were among reasons he was charged a higher premium – his insurer, Partners Life, reckons his costs were doubled because of those conditions.

But it wasn’t Partners Life who sold the policy. It is new on the scene after it took over the BNZ’s life insurance business on October 1. BNZ refuses to comment even though it sold the policy to the veteran in 2002 and managed it for 20 years until the end of September.

The veteran doesn’t recall the discussion that led to buying the policy. “They were all very helpful and obliging and it was reasonably priced,” he recalls.

It cost $431 each year for the original $10,000 cover. He does remember feeling pleased arrangements were made that would provide a financial cushion for his wife when he died.

As years passed, the value of the policy rose with inflation to being worth $15,151. It was the increasing likelihood of death which put his premiums into overdrive.

In September, he was told his premiums for the coming year would cost $6,754.54.

And that’s the point at which he quit the policy and asked for his money back.

Cash – over your dead body

Policies sold through banks make up 13 per cent of the New Zealand life insurance market, according to a Reserve Bank review published in 2020. It found it was also the most profitable part of the life insurance market, largely because of low overheads.

The veteran bought the policy in 2002 – aged 64 – because he was worried about leaving his wife without the benefit an insurance windfall would provide. With no children or other family, he wanted a safety net.

In the years since, he paid $43,000 in premiums to the BNZ’s insurance business. In the past three years, the veteran has paid more in premiums than the policy was going to pay out if he had died.

When the BNZ sold its business, it was the arrival of a new policy document seeking $5,800 in premiums and new letterheads which led the veteran to seek answers.

Until that point, fortnightly payments had simply been deducted from his account.

The annual letter from the BNZ’s insurance arm had told him his payments were increasing and said: “As you already have a Direct Debit Authority with us you do not have to do a thing – we will alter your Direct Debit to the new premium amount for you.”

And so the premiums rose and rose signalled by an annual letter from the bank. That was the extent of the contact until this year when the mounting costs and sale of the insurance business had the veteran telling the bank he had been conned and wanted his money back.

No, said Grant Leslie, the BNZ’s team leader for products and services. In a letter in September explained the policy he was paying for was the one he had bought and “BNZ Life are not obligated to refuse any premiums paid, nor make any payments to you, without a valid claim being processed and accepted”.

That’s to say, the BNZ would only return money to him over his dead body.

Leslie explained that his premiums meant he had “received the benefit of being covered in the event of … death” and that “life insurance policies are not an investment type of product”. They “are a legal product for sale in NZ” even though “they can become costly over long periods of time”.

“The decision whether to take up a life insurance policy and pay the premiums to retain cover over time … remains a decision for the customer.

“Please note it is prudent for a customer to review their banking and insurance needs from time to time and confirm anything taken up remains appropriate to the customer.”

Partners Life managing director Naomi Ballantyne said it was “entirely random luck” whether a policy paid out “after the customer has paid just one premium or after they have paid 20 years of premium”.

/cloudfront-ap-southeast-2.images.arcpublishing.com/nzme/B3IE7Z5NV2BSNMKIHMPNYV6IIA.jpg)

She saw the annual renewal process signalled the cost of the cover as “acceptable to keep the cover they wanted to maintain in place”.

“Effectively each year the client was advised of the premiums above through anniversary letters, and chose to pay the required premium to continue with the cover for the next year.”

Kris Ballantyne, the company’s marketing manager, describes the Kaitaia veteran’s decision to buy life insurance aged 64 as “rather uncommon … this late into life” but “not unheard of”.

At that age, the client would be beyond the main reasons people got life insurance – “to protect against premature, unexpected death” and the impact that had on a family’s expected earnings.

It meant the veteran was at the stage where premiums were beginning to rise to match the “significantly” increasing risk of having to pay out on it. As a point of comparison, claims risk and premiums between the age of 65 and 66 were comparable to that which occurred between 16 and 44.

Partners Life took a deep dive into the veteran’s file after questions from the Herald. In 2016, Kris Ballantyne says, BNZ told him that premiums would increase above and beyond the amount of money he would be paid out if he continued with the policy.

This puts the veteran in a position that was “quite unusual” as “we generally see covers being cancelled in accordance with … diminished needs, often around the age of retirement”.

Complaints by the veteran that he received nothing in return for what he had paid was “an interesting position”.

“We would suggest that not dying early in life is a good outcome, and having been financially protected in case you were randomly unlucky enough to trigger a claim, is also a good outcome.”

Tell people the ‘tipping point’

It’s an obvious principle – the older you get, the more likely you are to die and the more expensive life insurance will be.

It begs the question, says Retirement Commissioner Jane Wrightson, as to why no one picked up the phone and spoke to the veteran to ask if the policy still suited his needs.

“That’s a disgraceful story,” she says. “I would put anybody in their 80s in the ‘customers with vulnerabilities’ basket.”

That would mean having “careful conversations” with those people who held such policies. While taking care not to patronise, insurers should be asking why life insurance was bought in the first place and if it still served their needs.

“The question for him is ‘what does he want the policy for?’. If it’s to pay for his funeral, he’s wasting his money.

/cloudfront-ap-southeast-2.images.arcpublishing.com/nzme/5CNKJDAGBKZVBAX4SMYFWTFPOI.jpg)

“It’s incumbent on organisations to be aware of how to segment their customer base and relatively older customers need special care.”

There’s a question, too, over how the policy was sold and whether the veteran was told how much he would pay as he aged. “Clearly people are going to get old and die. The company would have known they were going to raise the premium in the way they did – but how did they tell him that?”

It’s not like companies don’t clearly understand the risk and reward calculation from the outset, says Age Concern chief executive Karen Billings-Jensen. It means initial conversations about life insurance should help the customer understand where the “tipping point” occurs.

For example, a young adult seeking life insurance might do so to cover mortgage payments and the needs of dependents. It should be clear from that early point that a mortgage that is on track and children growing to adulthood will each require less support 20 years on from a policy being taken out.

Without that conversation, she says those with life insurance can find they continue to hold a policy well beyond the point it is necessary. “There’s a sweet spot fort (the insurer) where suddenly they are making money hand over fist.”

Research from the Financial Markets Authority found 62 per cent of people do not have life insurance. People cited it as a low priority – and that they didn’t trust insurance companies.

In a speech to the Financial Services Council NZ – which has life and medical insurance companies as members – the FMA’s head of banking and insurance Clare Bolingford spoke of how three-in-10 of those with life insurance were not satisfied.

For a product sold to millions of people, that meant “a lot of people who aren’t satisfied”.

Bolingford’s speech spoke of the incoming Conduct of Financial Institutions regime which came out of a series of unflattering reviews of the New Zealand life insurance industry by the FMA and Reserve Bank.

Those reviews included finding there was “limited evidence of products being designed and sold with good customer outcomes in mind” and that “some insurers did little or nothing to assess a product’s ongoing suitability for customers”.

There appeared to be greater priority placed on incentive structures for those selling insurance than on good customer outcomes. In cases where policies were sold through an intermediary – like a bank – “there was a serious lack of insurer oversight and responsibility for the sales and advice and customer outcomes”.

Another review published in 2020 found New Zealand’s life insurance market to be “relatively inefficient” with “relatively low coverage of New Zealanders’ death and disability risks”.

The review found New Zealand life insurers paid out a relatively low proportion of claims (58 per cent) compared to overseas (79 per cent).

The review found life insurance sales made more money in New Zealand than in comparable countries even though our local market saw higher levels of expenses – including high commission rates and perks – pushed by insurance companies to those who sold their policies.

Bolingford’s speech described the new CoFI regime as one that prioritised “fair conduct” over “box-ticking compliance”.

/cloudfront-ap-southeast-2.images.arcpublishing.com/nzme/KDHVEOD7UVEFPPL5W6C3QSVPSM.jpg)

She told the Herald: “We actually have been signalling to firms they need to have more of a ‘whole of life’ relationship with their customers. That does mean connecting clearly and regularly with customers.”

Along with the new CoFI framework, the FMA has been studying insurers practices. In the last few years, issues found to impact on half-a-million customers have seen $43m paid in remediation and a host of yet-to-be resolved cases.

Financial Services Council NZ chief executive Richard Klipin says the questions for all consumers is: “What am I getting? What am I paying? Is the trade-off worth it?”

Those discussions start with people seeking insurance identifying the risk they are trying to head off. Klipin says there’s value continuing discussions with financial advisors on an ongoing basis.

“That shouldn’t be a ‘once and done’ conversation. It should be actively reviewed. Get good advice and guidance as you start your insurance journey and go through your insurance journey.”

Throughout those interviewed, there is a consistent message – get good financial advice. Banks are the expert advisors most people see regularly but there are others with financial literacy who provide services for nothing and take their income from the products sold to people.

“Take heart that the cowboys in the industry are no longer as prevalent,” says Insurance & Financial Services Ombudsman Karen Stevens.

Stevens talks about people having the right insurance product for the right stage of their life, avoiding “old policies that people have had for many years”. And it works both ways – not only do people want to know what their insurance company has to offer, the insurer needs to be updated in case health or circumstance has changed.

Here, again, she points to the role of financial advisors. “People who don’t have an advisor do it for themselves and are less likely to update or change policies.”

Massey University’s Dr Michael Naylor – a senior lecturer with its School of Economics and Finance – says most middle-class New Zealanders will not need life insurance once they pass the age of 50.

At that point, most will have security in housing or investments sufficient to provide a cushion should death suddenly come knocking. “Most people in this country have inappropriate insurance.”

For life insurance, Naylor says part of the issue is the product – it’s cover in case of death. “People don’t like to think about it. They buy it and do their best to not think about the things that could go wrong.

“You need a financial advisor to ask the hard questions. Most people should see a financial advisor – but they nearly all don’t.”

‘Hell of a life’

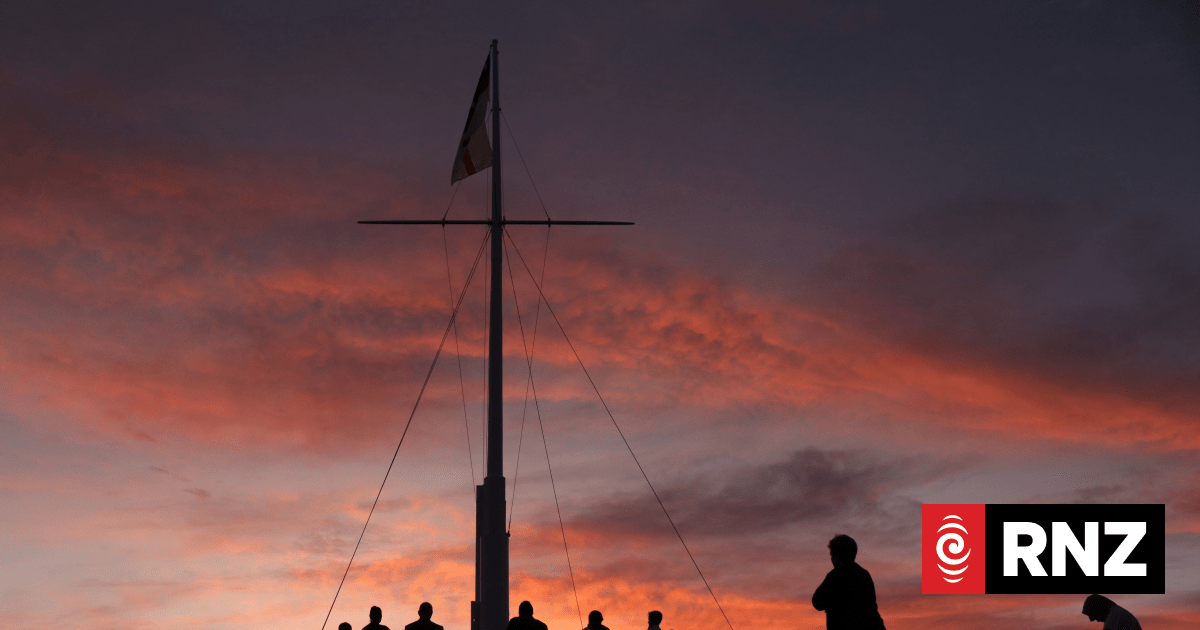

The Kaitaia veteran once lay in the dark of Vietnam’s jungles, sheltering under a poncho, waiting for the fight. He lay in the dark of the African bush, and the endless deserts of the Middle East, conflict just a moment away. “It’s been a hell of a life,” he says.

It was the Far North where he retired with the woman who spent much of their life waving him off to war. It was Kaitaia, at the local BNZ, where he bought the life insurance policy that eventually cost much more than it was worth.

Since then, annual letters recorded an incremental increase in premium. Time passed, marked by the few times a year he would stand to attention at remembrance services in April and November.

/cloudfront-ap-southeast-2.images.arcpublishing.com/nzme/IQXDP33NYNC6JEPJ6MZ7XPAMBM.JPG)

And here he is now, aged 84, having weathered another Armistice Day of sceptical looks at an unequalled rack of medals. Behind the medals are the memories that no one can shake, given the name PTSD years after the wounds were given.

“People would say, ‘you’ve got to move on. You’ve got to get over it’. But we’ve got to live with it. There’s no escape from it. It’s always there.”

When he opened the envelope and read his policy was going to cost close to $6700 for the coming year, the veteran’s inclination was to fight. He saw scandal and conspiracy and wrote letters to those he believed had done him wrong.

But it’s a different battle and there was no enemy. There was just the system.

“I didn’t know all this,” he says of the way premiums crept so high that he’s paid more in three years than the policy was ever going to provide.

The $15,000 would have paid for a good funeral and something left over for the wife he left behind, this time for good.

“I was hoping when I croak my wife would get that insurance money. But that’s not to be.”