More Kiwis will have to finance aged care privately if the current trend continues. Photo / 123rf

The crisis currently overwhelming the aged care sector is not an issue for the elderly anymore.

Bed shortages, an exodus of nurses searching for better-paid jobs, insufficient government subsidies – the list of challenges facing

aged care providers are ever growing and the sector is increasingly worried about how they can deliver services in the future – especially in regions like Northland.

If the trend continues, younger generations will struggle to finance age-related care and economists are advising anyone, no matter the age, to start thinking about their long-term finances.

A recent report by the New Zealand Institute of Economic Research (NZIER) that was commissioned by advocacy group Aged Care Matters says as house ownership numbers decline it will be increasingly difficult for people to pay for aged care.

For generations, Kiwis have paid for aged care by selling off their property.

Now fewer New Zealanders enter retirement mortgage-free, and over 20 per cent in the 60-64 age group don’t own a house at all.

Who can afford aged care?

“For regions like Northland, with high deprivation levels, it’s getting exponentially harder to afford aged care,” Aged Care Matters’ convenor and Heritage Lifecare chief executive Norah Barlow said.

“What worries the sector is what happens to those who can’t afford it.”

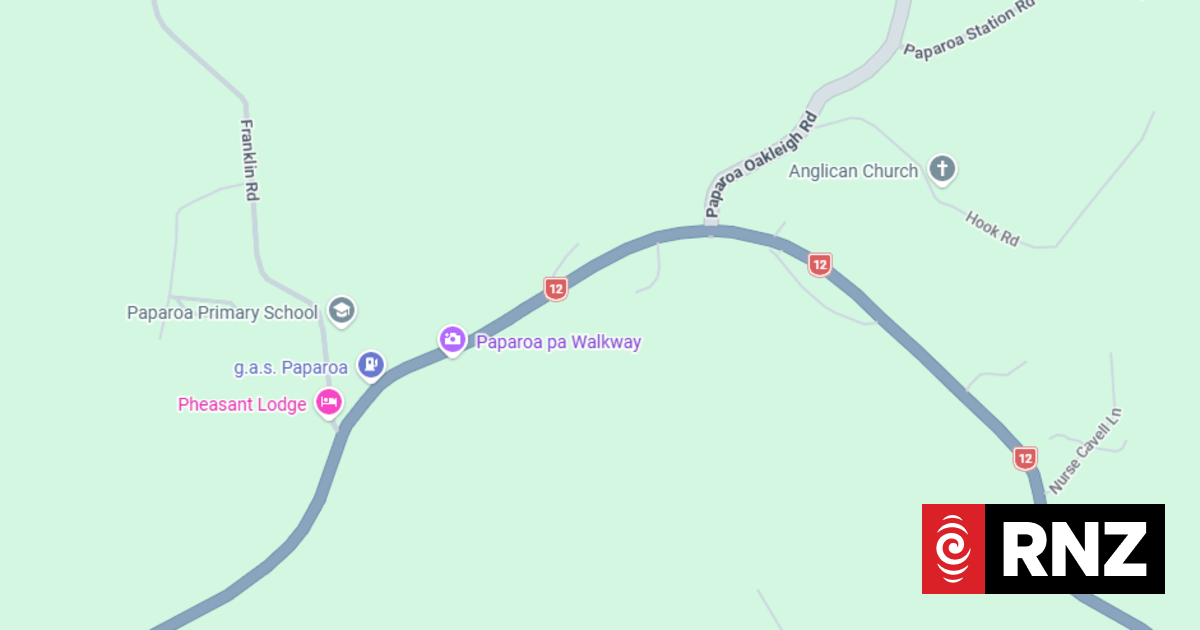

Older New Zealanders living in West Coast, Northland, MidCentral, Whanganui and Tairāwhiti are likely to be left further behind than their counterparts in other regions.

These are former district health board regions where more than 60 per cent of the population aged 85 and over are categorised as deprived.

Northland and the West Coast face additional struggles with having fewer dementia beds compared to other regions.

If no subsidised aged care beds are available, people are faced with either paying premium prices for beds or being cared for at home.

New Zealand has more people in aged residential care than most other OECD countries with 14.6 per cent of the population aged 80 and over receiving residential care.

However, the Government spends little on aged care compared to other OECD countries which will force more Kiw.is to rely on private finances.

/cloudfront-ap-southeast-2.images.arcpublishing.com/nzme/6GV6DY4GUM3SSH2I7EYFPIJYGA.jpg)

Age Concern Mid North manager Juen Duxfield confirmed that there are not enough beds. for people with dementia in the area.

“If people with dementia are not able to get a bed in a facility, they need care at home but that can be financially very difficult. It’s appalling.”

As for other aged care facilities, Duxfield said there was a limited supply for “those who have the means”.

“For people with less money there are more hurdles.”

She said often families had to step in and some became “trapped in the care for their loved ones”.

Older people have to go through a needs assessment to determine the level of care that would be funded by the Government.

The subsidy is also means-tested including both income and assets.

Residents are expected to meet the costs of residential care from their assets, and the limit on total assets is relatively low, $239,930 or less, reducing the eligibility for the subsidy.

There’s a cap for how much a resident will need to pay maximum for their bed if they have been assessed as requiring long-term residential care.

In the Far North and Kaipara, residents won’t pay .more than $1203.51 weekly for their bed; in Whangārei it’s $1230.39….

….

That means Northlanders pay up to $63,980, plus tax, a year for their aged care.

Building financial security for retirement

To avoid being at the mercy of government subsidies and undergo extensive assessment, more Kiwis are looking at their private finances to secure aged care for themselves.

Northland-born principal economist and director at Infometrics, Brad Olsen, says the earlier you put financial plans into place, the better.

“People can no longer finance their retirement with New Zealand super so they need to start thinking about their financial plans for the future as early as possible,” Olsen said.

It’s not only about planning but also investing and there are many investment options available – not only for those who earn top incomes.

Olsen said finances should be a conversation throughout life, from understanding the basics around money to meeting a financial advisor and considering investments.

“It’s a careful balance between saving for the future and having enough money to make ends meet.”

This was an “incredibly difficult conversation” to have with the current rate of inflation.

/cloudfront-ap-southeast-2.images.arcpublishing.com/nzme/ZNONJ3B23CAR7IHZDYDG5TVWMQ.jpg)

“In New Zealand, we often don’t make long-term plans. But it’s about understanding your financial position. If you get your general finances right throughout life, you are prepared for retirement and would have built those buffers you might need.”

Shortages back, right and centre

Meanwhile, efforts to improve the current funding system for aged care are slow going.

Beds become scarcer as the population is ageing and not enough aged care facilities are being built.

Aged Care Matters’ convenor Barlow said the only feasible option for developers to build new aged care facilities is by setting up a retirement village first.

That is likely because the Government funding model of aged residential care has not been revised since 2000.

A review was announced in 2017 but nothing further has happened since.

Barlow was disappointed that the Labour Government “that talks about equity and fairness don’t follow through with its promises”.

She said the sector has been working extensively with the Ministry of Health but it felt like aged care was “at the bottom of a pile of issues”.

For Puriri Court Lifecare Whangārei general manager Ruth McKenzie the crisis is fuelled by the nurse shortage.

She is currently only employing five registered nurses out of 12 job positions in the 72-bed hospital and rest home facility.

Following government regulations, McKenzie had to close beds. With aged care beds closed, more elderly end up in hospitals which puts further pressure on the clogged-up hospital systems.

/cloudfront-ap-southeast-2.images.arcpublishing.com/nzme/GKYX7BLBWE4LKF37UZKFDRYOIQ.jpg)

“Late last year it became quite evident. A thousand beds have closed New Zealand-wide. It’s a pay equity issue.”

Hospital nurses earn up to $20k-$30k more than aged care nurses.

Hiring new staff, including from overseas, is further complicated by lengthy immigration procedures.

“We offered signed employment contracts to eight international nurses in February. It’s August and we only have two of them here now.”

Aged care was on a negative downward spiral, McKenzie said.

Barlow concluded that no matter what is done for aged care, a lot needs to change and more money was essential to provide care for the elderly in the future.

One of the reasons why 89-year-old Far North resident Frances Halkyard prefers to stay at home. is her beloved garden.

“I’m not ready yet for a rest home. I love gardening,” she said. Besides, it was difficult to get a bed in a rest home, Halkyard said.

A carer is coming to see her in the morning and help her shower.

For the rest of the day, Halkyard’s grandsons take turns in looking after her.

Her “girls” are doing the shopping, but Halkyard still cooks by herself.

Ageing at home is an approach that has been increasingly favoured in recent years promoting the ability of older people to remain living in their homes and communities of choice whenever possible.

Far North health provider Te Hiku Hauora is delivering in-home support services, including personal attendant care such as dressing, grooming, bathing, personal hygiene, mobility and community interaction.

The Government-funded home support workers also help with the household, doing laundry, cleaning, grocery shopping and cooking as well as accompanying people to health appointments.

“Our service provides support to the elderly to enable them to live independently in their own homes,” Jill Edwards, Te Hiku Hauora manager for Disabilities & Home Support, said.

“It is harder to maintain a sense of independence and self when you are institutionalised, particularly if the decision to go into a home was not yours.

“By being supported at home, elderly people can continue living aspects of their previous life, surrounded by reminders of the life they carved out for themselves,” Edwards explained.

Person-centred care at home had a greater positive impact on wellbeing and happiness.

Support workers and clients are allocated geographically, but herein lies one of the biggest challenges for in-home aged care:

“Rural communities are diverse with small populations spread over large geographic areas,” Edwards said.

“Addressing the health needs of people living in rural areas is a critical challenge, particularly to meet the needs of people who are older and/or have a disability.”

As many Kiwis are reluctant to enter aged care facilities, can’t afford it or find no availabilities, in-home care provides an alternative for older people.

But home support also has its limitations: some people simply live too remotely, and others develop higher needs that exceed the care provided at home.

What’s the difference?

Retirement village: It’s a property development designed for retirees who want to downsize, but still live independently. There’s typically a range of accommodation types, as well as shared facilities such as gardens, restaurants and leisure centres. There is no government subsidy for purchasing a villa, apartment or unit in a retirement village.

Rest home/aged residential care: Aged residential care provides 24/7 care for an elderly person with a high-needs medical condition. They are generally for long-term stays and assist with all aspects of life, including bathing, dressing, medication and diet. To enter a care facility, a needs assessment must be done to determine whether rest home care or hospital level care is required. At rest home level care, people are looked after by one nurse. At hospital level, a second carer will be assigned.