Shane Reti symbolically breaks the ground for Whangārei Hospital’s new child health unit, with, from left, Health NZ Te Tai Tokerau operations director Alex Pimm, Health NZ head of infrastructure delivery Blake Lepper, and kaumātua Rex Nathan.

Photo: RNZ / Peter de Graaf

Health Minister Shane Reti says stage one of Whangārei’s hospital redevelopment is still on budget and on track to be completed by 2031.

Dr Reti was speaking at sod-turning ceremony on Friday marking the start of a new children’s outpatient clinic, which is due to open in mid-2026 at a cost of $35 million.

The budget for the entire stage one, as announced by the previous government in 2022, is $759m.

Dr Reti said staging the hospital rebuild meant Northlanders would be able to benefit from new, fit-for-purpose facilities sooner than if the whole redevelopment was built at once.

The other elements of stage one included a new Whānau House, which had recently been completed, and a new acute services building, which was currently being designed.

The acute services building, the largest and most critical part of stage one, would house a new emergency department, intensive care unit, radiology, and support services.

Dr Reti said Whānau House and Tira Ora, the new child health centre, had to be built first – because the old buildings were in the way of the planned acute services building, and because they had fire and health and safety issues.

Tira Ora would have eight consulting rooms, four treatment rooms, and support spaces such as playrooms and a gym.

That made it significantly bigger than the current children’s health unit, which had three consulting rooms and three treatment rooms, though some offices were also used for consultations.

It would be built close to the new maternity services building, Te Kotuku, and the two buildings would eventually be connected by a bridge for easy access.

Work on Tira Ora, which would be built on what is now a car park, could start as soon as next week.

Stage two of the redevelopment would entail building a 158-bed ward block or tower.

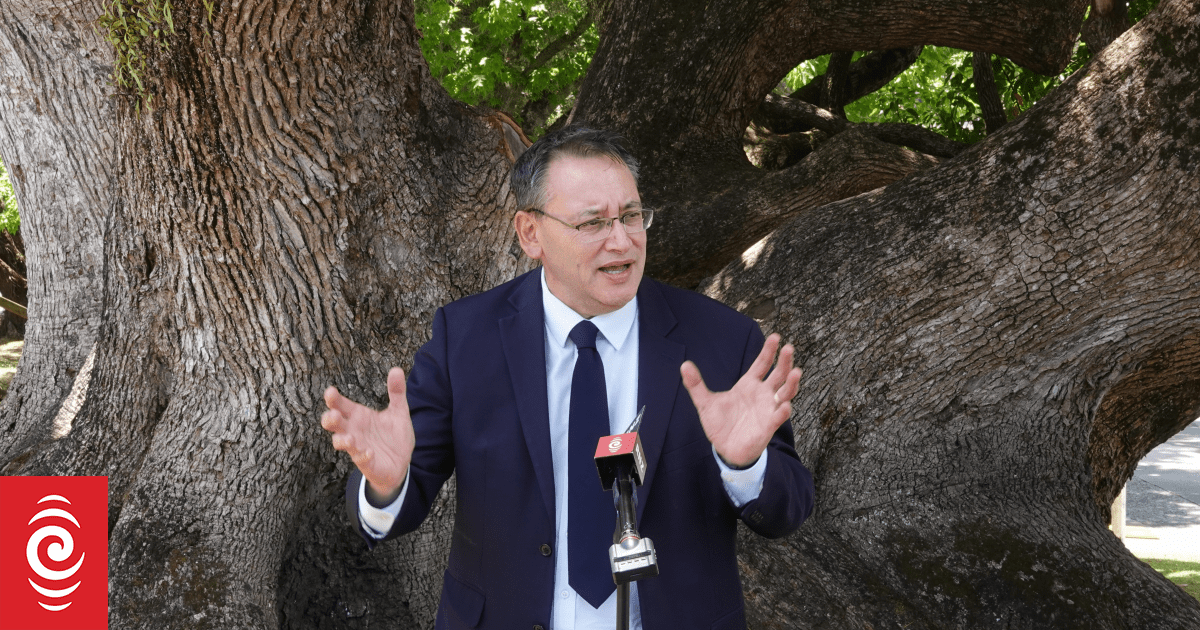

Health Minister Shane Reti speaks at the launch of Whangārei Hospital’s new child health unit.

Photo: RNZ / Peter de Graaf

Dr Reti said stage one funding included design work for the new tower but not the construction itself.

Until the design was completed it was not possible to give a budget or timeline for the tower.

Dr Reti said staging hospital developments with a series of smaller builds would help deliver new health infrastructure sooner, with greater certainty and on budget.

“Sequencing a build on a hospital campus like this will add capacity more quickly and allow the health system to build the right workforce to staff new or expanded facilities,” he said.

“This is a win-win. Staff can provide patients with the latest models of care sooner in modern facilities. It minimises disruption, and it’s more do-able from a construction, budget and workforce point of view.”

The existing hospital, parts of which date back to the 1950s.

Photo: RNZ / Nate McKinnon

In March this year, Health New Zealand gave the Whangārei Hospital redevelopment a red rating, which meant the project faced significant risks.

Those risks were a result of the costs of replacement car parking, an energy centre and an acute assessment unit not being included in the budget.

A dozen health projects around the country were given a red rating, including the Dunedin Hospital redevelopment.

The plans for the new Dunedin Hospital have since been scaled back, causing consternation in the southern city.

Dr Reti said, however, there were no plans to cut back the Whangārei project, which was still within budget despite some design challenges.

Parts of Whangārei Hospital date back to the 1950s and the Northland District Health Board, now Heath NZ Te Tai Tokerau, has been calling for new facilities since at least 2015.

Problems with the existing buildings include sewage running down the inside of the walls in the medical wing and leaks in the radiology department.

Earlier this year outspoken emergency doctor Gary Payinda said staff had to place buckets around million-dollar CT scanning machines to catch rainwater dripping from the ceiling, a situation he described as “just so sub-standard”.

Dr Reti agreed hospital buildings in much of regional New Zealand, including Whangārei, were a far cry from where they needed to be, and getting them up to scratch was a big task that had to be managed carefully.

Similar staged approaches to hospital redevelopment were planned in New Plymouth, Nelson and Hawke’s Bay.