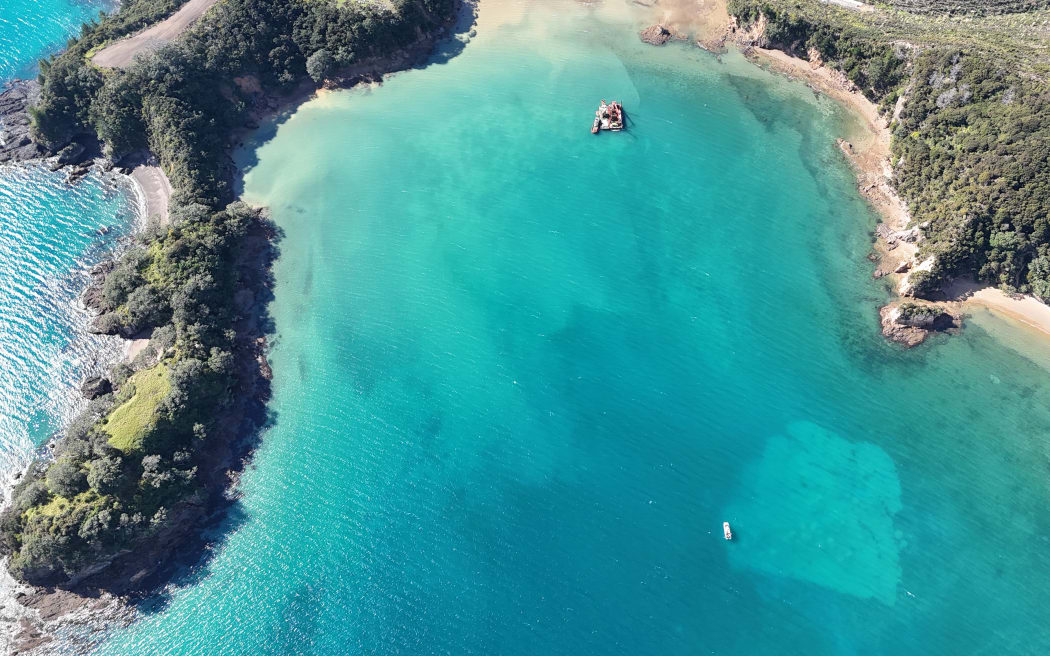

The redesigned caulerpa suction dredge in action in the Bay of Islands, with sand extraction trommels and a second barge for offloading one-tonne bags of caulerpa.

Photo: Supplied / Rana Rewha

Dredging of a highly invasive seaweed in the Bay of Islands could be complete by August – but only if the government stumps up another $5 million-plus for the biosecurity battle, a Northland council leader says.

Exotic caulerpa – described as the world’s worst marine pest for its ability to smother other underwater life – has so far been discovered at Aotea Great Barrier Island, in the Bay of Islands, and the Hauraki Gulf.

But it is only in the Bay of Islands where a concerted effort is underway to develop new technology for eradicating the fast-growing invader.

Those efforts hit a snag earlier this year when the purpose-built suction dredge was sucking up too much sand along with the weed, drastically slowing down the operation.

However, Northland Regional Council chairman Geoff Crawford said a redesign of the dredge had been a “game changer” with the machine now clearing half a hectare of seabed a day.

The aim was to increase that rate to a hectare a day.

About 60 hectares of Omākiwi Cove, near Rāwhiti in the eastern Bay of Islands, are infested.

Caulerpa growing on rocks in the Bay of Islands.

Photo: Supplied / Rana Rewha

Crawford, who also chairs the council’s biosecurity and biodiversity committee, said so much sand was being sucked up by the original dredge that the barge’s 100-tonne dewatering bag was full after just an hour’s operation.

It would then take up to two days, depending on the tides, to unload the barge.

The innovation by Russell marine engineer Andrew Johnson was to source two gold-mining trommels – rotating cylinders which use a mesh screen to separate materials of different sizes – and adapt them to separate sand from seaweed fragments.

Crawford said material sucked up by the dredge was now split into sand, which was returned to the seabed, and caulerpa, which was retained in one-tonne bags.

Once full, those bags were then lifted onto a second barge, which meant the operation could continue uninterrupted for eight hours a day.

“There’s very little sand coming on board now. The operation has probably gone ten times more efficient.”

The progress was down to Johnson’s “incredible number-eight-wire thinking”, Crawford said.

The current expectation was that dredging in the Bay of Islands could be completed in August, which he described as amazing news for Northland.

“It’s a game changer because we’ve got this, the first stage of eradication. We’ve come up with a plausible response and New Zealand should be very excited.”

The redesigned caulerpa suction dredge in action in the Bay of Islands, with the two large sand extraction trommels clearly visible.

Photo: Supplied / Rana Rewha

The dredge could potentially be deployed to Aotea Great Barrier next.

In February the government granted $5m to caulerpa projects around the upper North Island, with the bulk of that – $3.3m – earmarked for the Bay of Islands dredging trial.

However, Crawford said the funding would end on 30 June, and more would be needed to finish the job at Omākiwi Cove.

“We’ve asked for five or six million to finish it, which doesn’t seem like a lot of money for the threat that we’ve got. So we’re hoping the government will agree.”

Biosecurity Minister Andrew Hoggard told RNZ that Biosecurity New Zealand would review the trial data after late June or early July, and would then provide advice to his office.

Crawford said the long-term goal was to design a machine that could operate 24 hours a day and did not have to be unloaded.

“Then we’ll see some great efficiencies. We want to go 24 hours, because for every day we’re not there pulling out caulerpa is another day that it’s spreading. It’s a bit like having cancer.”

The regional council was aiming for eradication, and the current dredging operation was only the start, Crawford said.

The caulerpa suction dredge in action in Omākiwi Cove in the Bay of Islands. The clear patch at bottom right has been cleared of the invasive seaweed.

Photo: Supplied / Rana Rewha

A minimum 10-year surveillance and maintenance period would be needed to stop the weed returning.

“Because if the government isn’t going to commit to a 10-year minimum of surveillance and stopping re-invasion, we’re better off not spending a cent to start with, and just walk away.”

Crawford, a farmer with long experience of on-land weed control, said caulerpa reminded him of kikuyu grass.

Both covered large areas quickly by sending out long runners, could break off and spread via fragments, and had a way of re-appearing from nowhere.

“Kikuyu’s the most resilient plant I’ve ever dealt with. It’ll grow on top of a strainer post, just like caulerpa will grow on top of a rock.”

Regional council marine biosecurity specialist Kaeden Leonard said the trial using dredge spoil separators started on 6 May.

He was “incredibly encouraged” by the results.

“It’s a very novel approach, and it’s certainly scaling up our ability to tackle these types of marine pests. This has been a huge shot in the arm for marine biosecurity. Before this we’ve only ever had diver-assisted tools, now we’re going to more of a mechanical approach and really upscaling what we’re able to achieve.”

Leonard said the first version of the dredge was effective at removing caulerpa, but the retention of large amounts of unwanted material – such as sand, silt and shell fragments – made the process inefficient.

The redesigned caulerpa suction dredge with the two large sand extraction trommels clearly visible.

Photo: Supplied / Rana Rewha

Now sand and silt was returned to the seabed while anything bigger than 2mm was retained.

Independent scientists were regularly checking the dredge spoil to make sure no viable caulerpa fragments were released back into the bay.

While the dredge would be effective in most of Omākiwi Cove, other tools would be needed in rocky areas.

That could include hand-held suction devices and mats to starve the caulerpa of light.

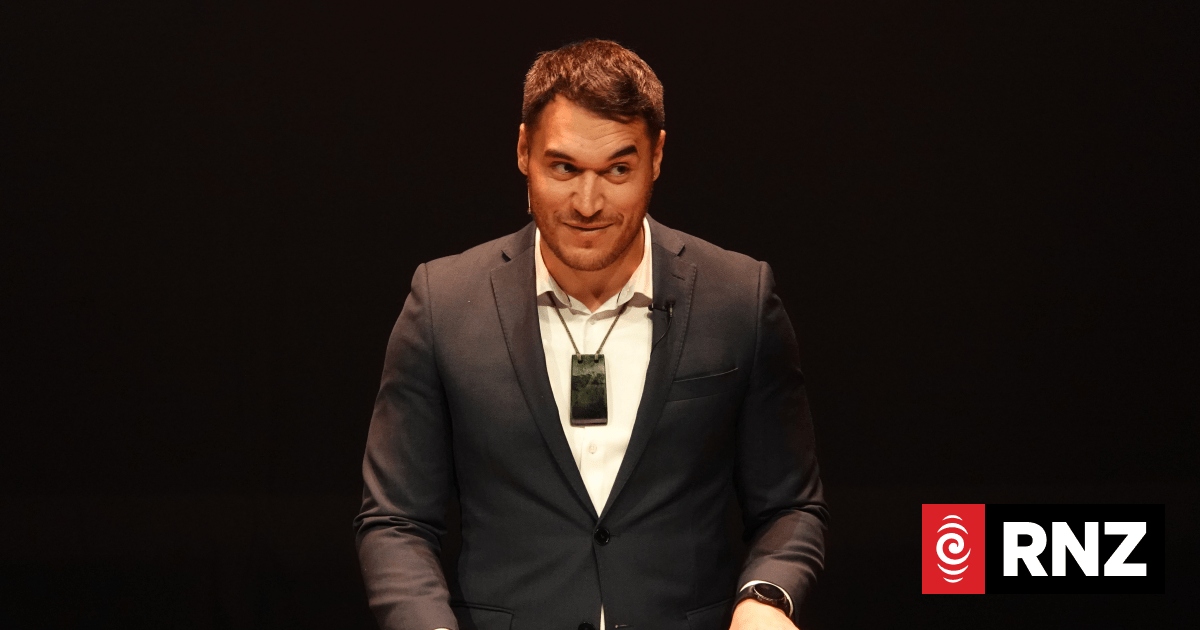

Meanwhile, a Far North couple instrumental in the Bay of Islands’ battle against caulerpa have won the country’s top biosecurity award.

Viki Heta and Rana Rewha (Patukeha, Ngāti Kuta) were named the winners of both the Te Uru Kahika Māori Award and the Supreme Award at last month’s New Zealand Biosecurity Awards.

Rewha was the first to discover caulerpa in the Bay of Islands, in May 2023, and both he and Heta are heavily involved in the response.

The Bay of Islands trial brings together, among others, local hapū, the Northland Regional Council, Ministry for Primary Industries, the Cawthron Institute, community group Conquer Caulerpa and maritime engineering firm Johnson Bros.

Caulerpa removed by the dredge is buried nearby on land. Biosecurity regulations prohibit moving the weed out of the affected area.