Part of the Enchanter fishing vessel which sank off the North Cape in March 2022.

Photo: Supplied / Auckland Rescue Helicopter Trust

The only passenger on board the Enchanter who saw a monster wave before it hit has given a harrowing account of the moments after the vessel’s capsize.

Peter “Shay” Ward, an experienced commercial fisherman from Te Awamutu, was one of eight friends who signed up for a five-day trip to the Three Kings Islands just over two years ago.

What was meant to be the fishing trip of a lifetime turned to tragedy when the Enchanter rolled and broke up as it was struck by a huge wave just off North Cape, with the loss of five lives.

The charter vessel’s skipper, Lance Goodhew, is currently on trial in Whangārei District Court on a charge of breaching his duties as a worker on the vessel, thereby putting people at risk of serious injury or death.

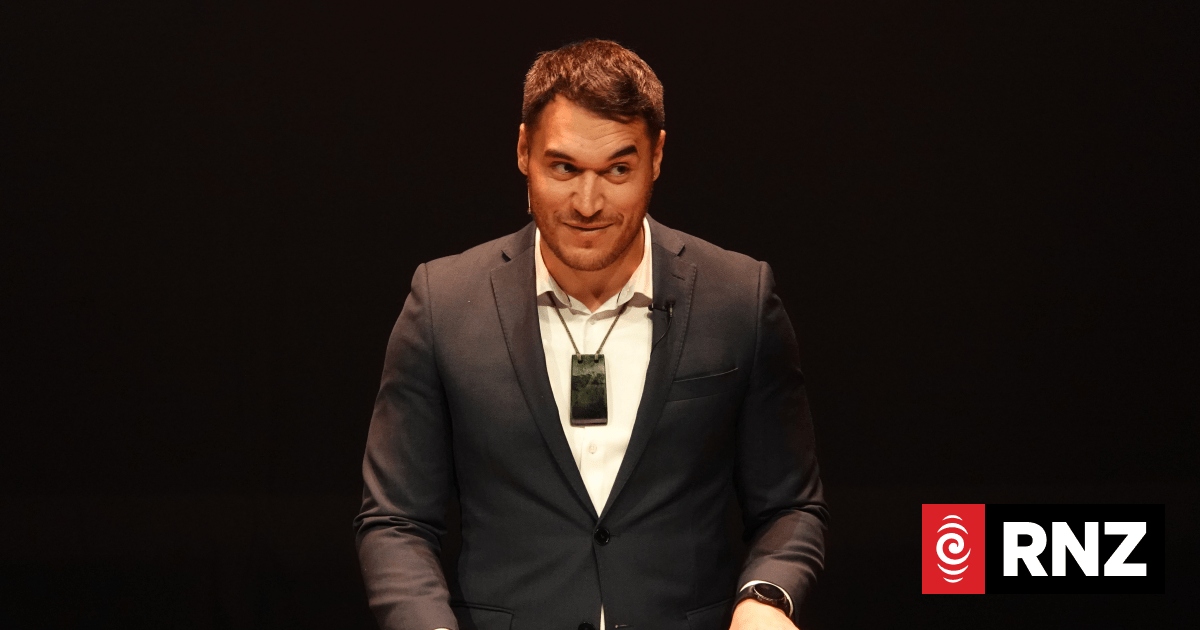

Enchanter skipper Lance Goodhew who is on trial over the sinking of the fishing vessel.

Photo: RNZ / Peter de Graaf

Ward told the court he was sitting on the rear deck on the evening of 20 March, 2022, as the Enchanter was nearing its planned anchorage for the night below the North Cape lighthouse.

At the time the wind was light, about 12-13 knots, and the swell about two metres, he said.

The other passengers were relaxing in the cabin so they didn’t see the wave coming.

“I remember seeing that swell coming in, and thinking, ‘f***, that’s a big swell’, but it wasn’t breaking, it wasn’t cresting, it was just a big swell,” Ward said.

“The boat went up the swell, and it went up and up, the boat rolled over, and I just expected the boat to roll back as we went over the swell, but the boat didn’t. That’s when I heard a whole lot of swearing and yelling and I’m assuming that’s when the breaking bit of the wave hit the windows. It was obviously just a big, steep, short, sharp swell, that crested and broke and hit us.”

Ward said he didn ot call out to Goodhew, who would not have had time to react anyway.

“It wasn’t a big wave I spotted way off in the distance, it just got big then and there.”

Ward said the wave was significantly bigger than the boat – “I had to look up to see it” – and estimated it was 10 metres high.

Along with the two crew and seven other passengers on board, Ward was thrown into the water.

“I rolled and rolled and rolled, I was expecting the boat to land on me, but it didn’t. When I stopped rolling I was still under the water. I got my jacket off underwater, I broke the surface and the boat was upside down, the props were going, black smoke, oil, debris everywhere,” he said.

Ward couldn’t see anyone else initially and assumed they were all still in the boat.

He swam to the rear of the upturned hull, where fellow passenger Mike Lovett joined him as he clung to the duckboard.

“I was by an exhaust so I was getting covered in black smoke and I didn’t want to climb up onto the duckboard because the props were still spinning. We waited until the black smoke finished, then I dragged myself up onto the duckboard. When that happened Kobe [O’Neill, the deckhand] appeared and Mike was face down in the water. Kobe wanted to resuscitate Mike so we tried to get him up onto the duckboard but we couldn’t … it was too late.”

Ward helped another passenger, Jayde Cook, climb onto to the hull, while Goodhew, O’Neill and Ben Stinson swam to the cabin roof.

The roof had been ripped off the vessel and was floating low in the water with waves washing over it, but it provided a platform the men could sit on.

Ward said he decided to stay with the hull because it was the biggest object in the water.

He called out to the passengers still in the water but they didn’t respond.

“They probably had a hell of a knocking around inside the boat when it went over. All three guys in the water were pretty expressionless.”

Ward himself had multiple fractures, broken ribs, and what he described as a hole in his leg, most likely from hitting the rail and rod holders as the vessel capsized.

The hull, the cabin roof and the men in life rings quickly drifted apart in different directions, and lost sight of each other in the fading light.

“For the first couple of hours we took a bit of a beating,” Ward said.

“As the boat went down and came up again a whole lot of water would rush down the hull and smash into us. I had a tourniquet, Jayde’s belt, around my leg to slow the bleeding a bit,” Ward said.

At one point Cook was washed off the hull by a wave. The boat was starting to list to one side so they moved to the other rudder and used the tourniquet to tie themselves to the propeller shaft.

After about two hours conditions started easing.

Ward and Cook spent four and a half hours clinging to the rudder before a rescue helicopter, alerted by the distress beacon that had popped out of the water next to Goodhew 15 minutes after the capsize, winched them on board and flew them to Kaitāia Hospital.

Ward said the weather at the Three Kings on 19 March had been “magic”, and that night the Enchanter anchored in the main island’s Little Bear Bay to shelter from the front passing over.

By about 9am on 20 March the wind had eased enough for the Enchanter to head for the Princes Group of islands for more fishing, and that afternoon they began the long journey back to North Cape.

Ward said there was nothing exceptional about the sea state or weather conditions at that time.

“There was a bit of roll, a bit of slop, but it wasn’t uncomfortable,” he said.

‘It was horrendous’ – skipper

The skipper of another vessel in the area, however, gave a different account of the conditions.

The skipper of the crayfishing boat Florence Nightingale, Matt Gentry was the last witness to give evidence on Tuesday.

He anchored in the next bay around from the Enchanter on the night of 19 March.

The next morning the wind meter on his vessel was recording wind speeds of 30-35 knots, though he said that could have been exacerbated by the island’s wind-funnelling effect.

Gentry estimated the swells rolling past the island’s northwestern tip were 3.5-4m.

He started checking cray pots on the morning of 20 March, but stopped after the vessel was hit by a large swell and backwash that smashed the TV off its mount and scattered food and plates around the galley.

Gentry opted to wait out the weather in a sheltered bay rather than keep working or try to return to North Cape that day.

“I would not put myself or my crew at risk. It was just rough as s***. It was horrendous. Generally, if we can’t work it, we can’t transit in it either,” he said.

Later, just before midnight on 20 March, Gentry had to make the transit anyway, after the Florence Nightingale and another fishing boat were called upon to join the search for survivors off North Cape.

Earlier on Tuesday, O’Neill told the court the wave that struck the Enchanter was “like being hit by a train”.

“I’ve never seen a wave like the one we took before, anywhere.”

Prior to the capsize he estimated the wind speed was about 15 knots and the swell 1.5-2m.

O’Neill said if the swell had been 3m, he and the others would have been swept off the cabin roof.

The judge-alone trial before Judge Philip Rzepecky is expected to take three weeks.

Gentry is due to continue his evidence today followed by the third surviving passenger, Ben Stinson, and the first of the expert marine weather witnesses.